Throughout human history, it has been common for certain behaviors to be considered normal and others abnormal. And yet, such distinctions have not always been made on the basis of medical knowledge, as they often are today. A new research paper, published in the Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, traces some of the ways that explanations for mental distress have changed over time, setting a historical context to think about how biomedical explanations for behaviors have become so popular.

Specifically, the article examines how biomedical characterizations of mental disorders—e.g., thinking about distress as ‘mental illness’—relate to beliefs and attitudes about those who have received a diagnosis. According to the two authors, led by Matthew Lebowitz from the Center for Research on Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications of Psychiatric, Neurologic, and Behavioral Genetics at Columbia University Medical Center, a biomedical explanation of mental disorders can be understood as:

“An account of the nature of mental disorders that casts them as medical diseases with biological roots, such as in genes or neurobiology,” adding that such explanations “are often seen as being in competition with other explanatory frameworks, such as those that conceptualize psychiatric symptoms as reactions to environmental factors or as traceable to early childhood experience.”

The authors situate their study within a growing body of literature that suggests that mental health clinicians are more likely to assume psychological distress is caused by biological factors than other possible explanations. Their paper argues that privileging biology over other causes has significant consequences for clinical decision-making practices, while also affecting how diagnosed individuals understand themselves through their diagnoses.

This comes at a time when criticism of biomedical approaches to mental health care is steadily mounting, with even members of the United Nations expressing concerns. Likewise, this publication comes on the heels of recent research suggesting biomedical explanations for psychological distress can stigmatize individuals, especially young people, who elect to use mental health services.

Lebowitz and Applebaum focus primarily on four different areas of research about how mental distress and abnormal behaviors tend to be understood: 1) a history of changing explanations for psychological distress, 2) theoretical and conceptual issues underlying biomedical explanations, 3) empirical evidence about the effects of biomedical explanations, and 4) developing strategies for countering the negative social consequences of the now dominant biomedical paradigm.

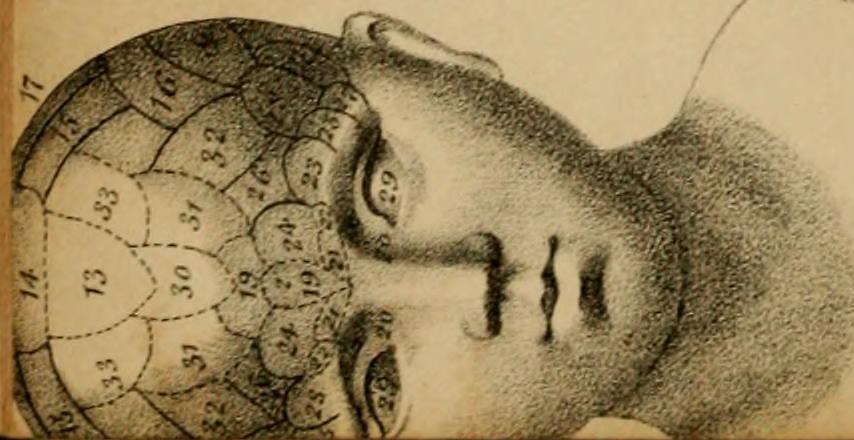

As is common in historical accounts of Western psychiatry, the authors trace the current biomedical model to the ancient Greek physician, Hippocrates, and his theory of humors. His framework, they suggest, offered a set of natural explanations for deviant thoughts and behaviors in lieu of the supernatural ones that were most popular up until that point.

With the Renaissance period of European history, they explain, came a revitalization of supernatural explanations, whereby “people exhibiting mental or behavioral disturbances were once again viewed as under the influence of demons or were even executed as practitioners of witchcraft.”

Later on, around the turn of the nineteenth century, trends reversed course yet again as “other areas of medicine were being revolutionized by biological discoveries, and psychiatry was suffering from diminished standing as a profession because of its failure to make similar advances.”

Going further, they outline how:

“[a]long with frustration over the lack of efficacy of existing treatments, this may have helped set the stage for the field’s twentieth-century embrace of psychobiological treatments that are now seen as barbaric, such as prefrontal lobotomies, the removal of healthy ovaries to quell hysteria, and the use of insulin-shock therapy as a treatment for schizophrenia.”

Despite being no longer deemed appropriate forms of treatment, such practices remain important historical footnotes insofar as they served to legitimize the profession of psychiatry in the eyes of the broader public. This trend toward the biomedicalization of psychological life continued across the twentieth century, hitting a high point with the emergence of psychopharmaceutical interventions in psychiatry.

Citing “data from nationally representative surveys in the United States,” for instance, the authors note that during “1998 most patients undergoing mental health treatment received psychotherapy, either alone or in combination with medication; however, by 2007 the majority received only medication.”

Today, the use of pharmaceuticals as interventions for psychological distress has been challenged increasingly by general practitioners, clinicians, and clinical researchers. Research approaches like Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), however, indicate renewed attempts to ground explanations for deviant behaviors in biology and medicine.

Drawing on a large body of research, the authors underscore how the biomedical model of mental health care can sometimes increase stigma for diagnosed individuals in the following four ways: 1) marking a clear dividing line between those with a diagnosis and without one, 2) stereotyping those with a diagnosis as inherently more dangerous, 3) positioning those with a diagnosis as part of a certain ‘out-group,’ and 4) leading to discrimination and socioeconomic disadvantage for those so diagnosed.

For Lebowitz and Applebaum, underscoring how these associations are made is important because there is a long history of mental health professionals assuming naively that biomedical explanations always decrease stigma for those diagnosed. Such a belief is summarized by the following quote from Eric Kandel, a psychiatrist who was part of anti-stigma efforts organized by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation in 2013: “Schizophrenia is a disease like pneumonia. Seeing it as a brain disorder de-stigmatizes it immediately.”

Attempts to link psychosocial distress to biological causes are often pursued under the assumption that this will help remove responsibility from the diagnosed individual similarly as it would for other physical diseases. For the authors, this is closely connected to the presumption of categorical essentialism, defined as the“belief that underlying essences (e.g., genes, neurobiology) define categories (e.g., social groups) and deterministically cause surface-level similarities among category members.”

According to Lebowitz and Applebaum, however, a growing number of studies suggest a much more complicated relationship between essentialism, biomedical explanations, and social stigma. As they describe, not only do “biomedical explanations of mental disorders show a small but significant association with increased perceptions of dangerousness,” they likewise tend to “evoke essentialist biases and lead to the assumption that mental disorders are relatively immutable and unlikely to remit.”

These conceptual links can have consequences well beyond how the general public perceives diagnosed individuals. They also affect how clinicians interact with such individuals during treatment.

In one study overviewed by the authors, for instance:

“When clinicians were given a biomedical explanation of a patient’s symptoms, the clinicians consistently rated psychotherapy to be less effective, and with one exception (schizophrenia, for which ratings of the effectiveness of medication were about equally high regardless of the explanation provided), they rated medication to be more effective.”

In other words, even clinicians were more likely to assume that pharmaceutical intervention is the best option when biomedical explanations are the only ones offered for observed symptoms. This has clear implications for thinking through why particular treatments become more popular than others in general.

While clinician’s beliefs about diagnostic categories are undoubtedly important, the authors affirm that “people’s attitudes and beliefs about their own disorders are likely the most clinically meaningful of all.” And yet, they suggest research linking self-stigma to biomedical explanations appears inconsistent, at best, depending mainly on how each person internalizes such explanations.

The authors remain clear on the fact that beliefs in genetic predispositions for psychiatric diagnoses, overarching essentialism, and self-blame reinforce each other in ways that harm diagnosed individuals. They also expressed optimism that “[e]ducation about the nondeterministic role of biological factors in the etiology of mental disorders appears to mitigate some of the negative effects of biomedical explanations.”

Likewise, while they concede that “economic considerations and other factors clearly play a part in the selection of treatments,” they stress the importance of understanding “whether the recent ascendancy of biomedical explanations for mental disorders might be encouraging the use of pharmacotherapy and the rejection of psychotherapy.”

This last point, however, can be read as a notable limitation of the perspective taken by the authors of this article. Many researchers today would consider it impossible to understand how psychotherapy and psychiatry operate socially apart from capitalism and neoliberal policy. For instance, contemporary mental health markets in America unavoidably cater to insurance companies and pharmaceutical industries, which unavoidably structure how services are provided.

With mental health treatments increasingly shifting online, moreover, the relationship between mental health care and capitalism is likely to be reinvented in more complex forms—leading to new markets for clinical data and advertising for mental health services.

Lebowitz and Applebaum’s hesitation in rejecting biomedical explanations wholesale appears to be based on their commitment “to the promise of biomedical advances for aiding the field’s understanding of psychopathology.”

This reveals an overarching belief on their part that biomedical approaches in psychology and psychiatry can be useful for reasons other than legitimizing psychopharmaceutical treatment. Regardless of their position on this particular issue, however, their article underscores important conceptual links between how psychological distress is framed linguistically and how those who receive services are treated socially.

****

Lebowitz, M. S., & Appelbaum, P. S. (2019). Biomedical Explanations of Psychopathology and Their Implications for Attitudes and Beliefs About Mental Disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15(1), 555–577. (Link)

Removed for moderation

Report comment

Mental diseases definitely have a biological basis, arguing with this is unproductive.

But it is such a loose concept. For example, you drank coffee and the brain is already working differently. Or an adult person has the intelligence of a 5 year old child. Psychiatrists decided to combine these two cases and give people the same diagnoses (schizophrenia). This is not discrimination. This is a strategy.

Report comment

There was nothing wrong with viewing ‘abnormal’ behaviors as supernatural, when the culture doing so did not also automatically assume that supernatural things were also scary, evil, dangerous. There were times and cultures where people understood supernatural to mean “something unusual, that only certain people are capable of,” and usually it was after coming close to death and living through the injury or illness. Remove the dirty lens of evil that religion places over the supernatural, and look through the lens of tribal cultures and you see a shaman, one who can walk between the worlds, and speak with the dead, and see visions of times/places not present. These individuals were valued, they were acknowledged as having access to sources of information the average person did not. And when they shared their visions, their wisdom, the community respected their words and their ways. It would be unthinkable to dismiss a shaman’s wisdom, disregard them as senseless, worthless, etc.

Turning away from this reality has dismembered us as a species; we are maybe half as human as our ancestors who understood this.

Report comment

I love this post!

Report comment

LavenderSage, you are absolutely right. Our society has been glorifying the evil, while defaming, poisoning, and silencing the “insightful,” “prophetic,” and “too truthful” people for decades, or longer.

Report comment

Psychiatry also seems to miss the fact that the only reason they exist at all is because of genetic diversity.

The genetic diversity breeds some undesirables who bring misery and chaos to peaceful types.

Report comment

Your essay is actually on pharmaco-medical medicine and psychiatry. “Biomedical” psychiatry also gets to confuse itself with neurology, which few psychiatrists actually seem to understand (but what their premises would seem to suggest is that they actually comprehend the subject well).

Report comment

Thank you bcharris,

There is a massive problem with DISCIPLINE confusion. Very serious neurological diseases, conditions, illnesses or insults or diseases with neurological involvement can and do end up in psychiatry. If you asked a Psychiatrist to label the different parts of the brain and what each part is responsible for, they could not. If a patient has a Silent Stroke which means they would slur their words, be in pain, struggle with senses of touch as well as cognitive function, a psychiatrist would they be able to distinguish and know that person needs Medical Attention rather urgently. Of course, not. A DSM label would be slapped on and the patient does not want to ‘Get Better’. They need these anti-psychotics, mood stabilisers and possibly, anti-depressants. No, they are physically disabled and more likely to have another Transient Ischaemic Attack or Haemorrhage. The fact the first was misdiagnosed and mismanaged making them more susceptible to the second insult means is a Psychiatrist COMPETENT ? Can they distinguish between very REAL medical events and Mental Health. The answer is NO. So, their over-riding desire to SAVE patients has gone dreadfully wrong. The Act of Omission is rather a big deal.

Report comment

The Biomedical model leads to Stigma and Discrimination, as also does the entire concept of Mental Health.

But also the Moral Improvement and FYOG model also leads to Stigma and Discrimination, as also does the Neurological Difference and Diversity model. And it is these latter which we find being promoted on this forum.

Report comment

It was a relief to me when I found the Biomedical model had no basis. That people like me were not monsters after all and the drugs really were messing up my thinking. (Not imagining it or faking the Parkinsons and seizures.)

Like that scene in T.S. Eliot’s The Cocktail Party where the woman is glad to know things are (partly) her fault because she can change them after all.

Psych “diagnoses” are unduly pessimistic and lead to us being treated worse than convicted felons. But they help shrinks and groups like NAMI make money and maintain political clout. So they will keep promoting them unless forced to stop.

Report comment

Sorry to learn you have Parkinson’s disease and seizures. Nobody asks for these hideous Neurology diseases. Wishing you all the best, Rachel777.

x

Report comment

Rachel777, But the idea that things were “partly her fault because she can change them” is just another form of manipulation. “Everybody needs Recovery” is just Rick Warren’s new version of Original Sin.

I am involved in local efforts to counteract the actions of the Evangelicals and their outreach ministries.

I am always telling people, that if someone has been treated with dignity and respect, and given the chance to develop and apply their abilities, then it is very unlikely that they would ever have developed a serious problem with alcohol or drugs.

And with my Pentecostal Molester I did my best to argue to the court that unless he gets an adequate sentence, then there is no reason to expect more survivors to compromise themselves by coming forward.

And then I spoke of that church’s outreach ministry, telling the poor and the homeless that Jesus has so much compassion for them that he wants to give them a second chance. All he wants in return is that they admit that it is their fault for screwing up the first chance.

And then I pointed out that if these girls had not come forward in defiance of their church and their parents, and told the truth, who knows what could have happened. Failed marriages, failed attempts to get an education and build a career, and some years down the road, they could have been the next clients for that church’s outreach ministry.

Report comment

K

Report comment

Definitely the religions joined forces with the “mental health” workers, whose primary societal function is covering up child abuse and rape, long ago.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

They’re even teaching the DSM “bible” in the seminary schools today. I’ve learned that child abuse survivors, and their parents, are not welcome in my childhood religion, so much for that pesky little thing called Christian theology. Even the bishops of that religion are child abuse cover uppers.

https://www.amazon.com/Jesus-Culture-Wars-Reclaiming-Prayer/dp/1598868330

https://virtueonline.org/lutherans-elca-texas-catastrophe-coming-lesson-episcopalians

A pastor from another religion confessed this medical/”mental health”/religious child abuse and rape covering up, systemic “conspiracy” against child abuse survivors and their families, to be “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions.”

Apparently the pastors, bishops, and doctors didn’t have the foresight to realize that if they created a multibillion dollar, scientific fraud based, primarily child abuse covering up, group of “mental health” industries, they’d end up aiding, abetting, and empowering the pedophiles and child sex traffickers? So pedophilia and child sex trafficking are now big problems in Western civilization.

https://stream.org/trump-signs-anti-human-trafficking-legislation-reauthorizing-key-law/

https://www.sott.net/article/345836-PedoGate-Update-The-Global-Elites-Pedophile-Empire-is-Crumbling-But-Will-it-Ever-Crash

Let’s hope America actually starts arresting the child abusers, and gets the “mental health,” “social services,” CPS, foster care workers, pastors, and bishops out of the child abuse and rape covering up business. The IL State Attorney’s Office is finally looking into the Catholic child abuse scandal. But it’s not yet looking into the ELCA Lutheran religion, and their DSM deluded social service workers’, systemic child abuse covering up crimes. Child abuse covering up crimes which are inevitable because the DSM is a child abuse covering up system, by design.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

Report comment

In addition to the medical and supernatural explanations, the ‘philosophical’ explanation, was a solid contributer in the classical times in regard “deviant” thoughts and behavior. This is illustrated by the force against Hippocrates and his supportes laid down by a great number of Plato’s dialogues (Levin, 2014). To write the history as a war between biomedical and supernatural explanations when there is clearly more to it than that, is unfortunate, and may favor the biomedical in lieu of other natural explanations.

Reference: Levin, S. B. (2014). Plato’s Rivalry With Medicine: A Struggle and Its Dissolution. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press.

Report comment

The dogmatic proponents of each viewpoint have intentionally created this dichotomy, so that it sounds as if there is a choice between doing what they believe in or doing nothing or something stupid. It isn’t a real dichotomy, but a lot of people have a hard time with uncertainty.

Report comment

I agree 100% with Someone Else, and great links too.

And I want to emphasize that it is not just Psychiatry and the Biomedical Model. Psychotherpy has always worked like religion. It runs on a Moral Improvement Model.

Freud got his approval and social standing by selling out his patients, female ~hysterics~, and saying that they were lying or fantasizing about early childhood sexual molestation.

Now today, there would be consequences if a therapist tried to do that, call the client a liar. But they still take the position that though they believe what you are saying, that it still does not rise to the level of anything which you need to do anything about. So they are dismissing it, taking on the role of a judge, and deeming that you have no case.

Psychotherpy and the Recovery Movement have painted the picture that childhood trauma is harmful because it creates memories, and then that the harm is in these memories. And these memories exist like a film of events. It might be conscious, or following Freud, it might be unconscious.

But this is a horrible and no longer applied model of cognition. It seems to go back to John Locke.

“He offered an empiricist theory according to which we acquire ideas through our experience of the world. The mind is then able to examine, compare, and combine these ideas in numerous different ways. Knowledge consists of a special kind of relationship between different ideas.”

https://www.iep.utm.edu/locke/

So your therapist will try to surface these memories. They used to try to eradicate them. But this is less and less. But it is still completely faulty. You have to look at the entire course of your life and at your present experience, to see how abuse and trauma has effected. Most of the time what it does, consisting of betrayal, is it limits your social options. So it makes it harder to form intimate relationships, it makes it harder to get an education, and it makes it harder to build a career.

If people understood how much the course of their life had been shaped by lies, denial, hypocrisy, and betrayal, the they would be leading the charge to hold perpetrators accountable.

But we don’t see this, instead we see survivors echoing the language of psychotherapy and recovery, “healing” “leaving it behind” “forgiveness”, and acting like nothing happened. And the reason for this is that your psychiatrist needs to protect their own denial systems. And the whole basis of their profession is that just by manipulating the victim, the wrong is corrected.

They like to say in Recovery programs, “the only person you have control over is yourself”. And this is totally untrue. I helped 3 girls get their father a long sentence in our state prison. A local attorney got a woman a $500k judgment against a childhood sexual abuser.

Here, Hubert Dreyfus, an expert on Heidegger and Existentialism shows that both Freud and Edmund Husserl studied under the same Franz Brentano. And they each came to represent different paths. Then following from Husserl to Maurice Mearleau-Ponty he shows us a different way of relating to ~Psycho Pathology~.

https://web.archive.org/web/20061214214634/http://ist-socrates.berkeley.edu/~hdreyfus/html/paper_alternative.html

Of course I am not endorsing any idea of ~Psycho Pathology~, but I am simply saying that to appreciate how much one’s life has been effected by trauma, one has to completely deconstruct ones self. Just coming up with a film of events does not in anyway come close.

And then the most severe abuses will usually be coming from primary care takers, and they amount to serious betrayal. Most middle-class child abuse ( physical, emotional, medical, and sexual ) are being rationalized as necessitated by the Self-Reliance Ethic. Being able to do this and to create for themselves an unstigmatized adult identity will usually be why the parent decided to have children in the first place. And for the most part our society exonerates them, and this will be continuing as you walk into your psychotherapist’s office.

We should not be talking with psychotherapists, or clergy, or psychiatrists.

A better model of cognition:

https://www.amazon.com/Tree-Knowledge-Biological-Roots-Understanding/dp/0877736421/ref=pd_lpo_sbs_14_t_1?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1&refRID=XBHDRNJT08771NXD57ZS

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0262720213/ref=dbs_a_def_rwt_bibl_vppi_i0

And about this idealized autonomous subject which conservative political theory tends to create:

https://www.amazon.com/Anti-Social-Family-Radical-Thinkers/dp/1781687595/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=anti-social+family&qid=1563834181&s=books&sr=1-1

And then about how Jefferson was breaking with one of his intellectual mentors, John Locke, in his preamble:

https://www.amazon.com/God-Other-Famous-Liberals-Reclaiming/dp/067176120X/ref=sr_1_4?keywords=f.+forrester+church&qid=1563834236&s=books&sr=1-4

And before I forget, how to people feel about a movement to label children with ~neurological difference~, and then to be telling them to build their lives around the doctrine of Cognitive Liberty and the concept of ~neurodiversity~?

Report comment

Removed formoderation

Report comment

So fortunately now some have started to file lawsuits against Psychotherapists, and it sounds like large sums of money have been recovered.

MIA should be the central information node for promoting such lawsuits.

Report comment

Biomedical Model is no good, but so also is the Psychotherapy Model, uses rotten model of cognition.

https://web.archive.org/web/20061214214634/http://ist-socrates.berkeley.edu/~hdreyfus/html/paper_alternative.html

We should not be going along with any model of ~mental or moral illness~

Report comment

Is invading lands and making crooked deals with indigenous people a mental illness?

Is taking their kids and forcing them to adopt the right way, a mental illness?

Psychiatry and it’s shiksa, the doctor, are simply eugenics at work. They evolved from privilege.

Report comment