Audio: Listen to this report.

Although the general story of ghostwriting in trials of psychiatric drugs is now pretty well known, the details of the corruption in specific trials are still emerging into the public record, often a decade or more after the original sin of fraudulent publication. The latest study to finally see the full light of day is GlaxoSmithKline’s study 352.

Perhaps the most infamous ghostwritten study is GSK’s study 329, which, in a 2001 report published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, falsely touted paroxetine (Paxil) as an effective treatment for adolescent depression. The company paid over $3 billion in penalties for fraud.

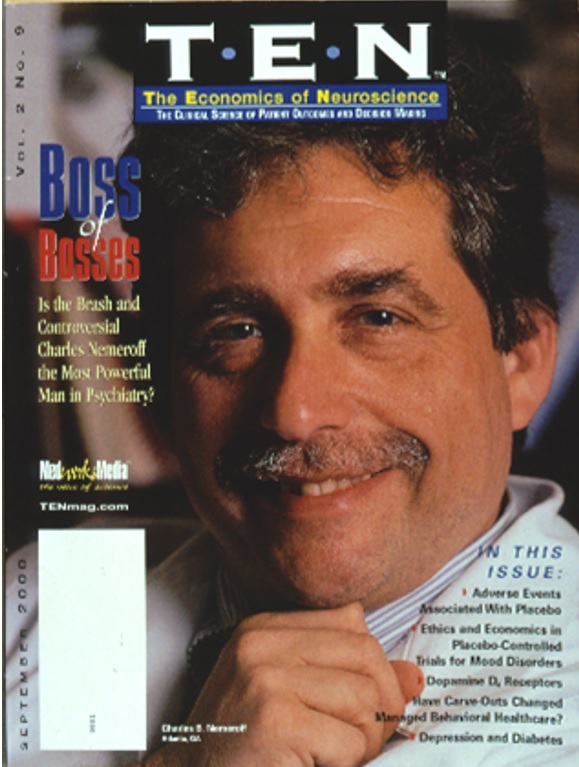

That same year, study 352 made its first appearance in the research literature. That was when Charles Nemeroff, who in the years ahead would become the public face of research misconduct, “authored” an article on the efficacy of paroxetine for bipolar disorder. It has taken 18 years for the full story of that corruption to become known, the final chapter recently emerging when a large cache of study 352 documents—emails, memos, and other internal correspondence between the key players—was made public.

The documents reveal a web of corruption that went beyond the fraud of ghostwriting into the spinning of negative results into positive conclusions, and the abetting of that corruption by an editor of the scientific journal that published the article. The documents also reveal a whitewashing of the corruption by the University of Pennsylvania.

However, it was the publication of these documents that provided Jay Amsterdam, an investigator in the trial who turned whistleblower after he smelled a rat, with a chance to say “case closed.” Amsterdam and Leemon McHenry have now published two articles that provide a step-by-step deconstruction of the study—the ghostwriting, the spinning of results, the betrayal of public trust.

Here is the story of that whistleblowing.

The Whistleblower

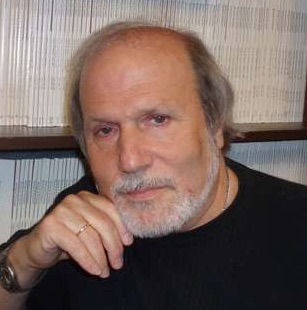

Starting in the late 1970s, Amsterdam became a go-to guy for studying pharmaceutical interventions, especially antidepressants. By the time he got involved with study 352, he was running a prestigious bipolar disorder clinic at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. He’d published over 100 peer-reviewed articles, and had served as editor and author on multiple textbooks about mood disorders. He was a working psychiatrist, a lecturer and professor, and a full-time researcher.

Amsterdam received his MD in 1974 from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. While still a post-doc, he began working almost immediately with the top researchers investigating treatments for mood disorders. William Dyson—one of the early promoters of lithium for bipolar disorder—was one of Amsterdam’s mentors, as was Dyson’s colleague, Joseph Mendels. Dyson opened the bipolar disorder clinic that Amsterdam would eventually run.

In the early 1980s, hormone function was one of the chief hypotheses in mood disorders, and Amsterdam became a leading researcher in the burgeoning field of psychoendocrine studies. He conducted a number of studies on melatonin, among many other hormones. By the mid-1980s, Amsterdam was working under Karl Rickels, an ex-Nazi soldier who had been one of the chief investigators on pharmacological treatments for mental health since the 1950s. Amsterdam describes Rickels as a brusque, almost abrasive figure who worked almost exclusively with pharmaceutical industry money, investigating the efficacy of the drugs, but who remained proud of the fact that he did not have his papers ghostwritten. “You should always write your own articles,” he told Amsterdam. “You know, no one has ever written an article for me.”

During this time, Amsterdam was investigating various pharmaceutical treatments for depression and bipolar disorder, including tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, and newer SSRI antidepressants like fluoxetine (Prozac). By the late 1980s, Amsterdam had become a leading researcher in psychoimmunovirology, conducting some of the earliest studies on the hypothesis that exposure to viral disease was a cause of psychological disorders. While it’s unlikely that this is a cause for most psychological problems, some viral diseases like the Borna disease virus and the Epstein-Barr virus have been correlated with a slight increase in the likelihood of psychological problems. He began studying whether lithium might work by suppressing the effects of viral disease.

By 1993, Amsterdam’s mentor Dyson had passed away, and Amsterdam became the director of the bipolar disorders clinic at Penn. At the time, his clinic was a perfect fit for the needs of the pharmaceutical industry. It was large, so he had a pool of potential participants for trials. Amsterdam also describes the clinic as offering access to treatment-naïve, or drug-free, patients with depression and bipolar disorders, who were good enrollees in industry studies.

Amsterdam was happy to work with the industry at that time. One year, he offered his entire crop of mood disorder research participants to Eli Lilly for their study on fluoxetine (Prozac) for relapse prevention. According to Amsterdam, he told them they’d have to pay all his operating costs for the year. “We’ll take care of you,” Lilly’s spokesperson responded. Amsterdam says, “I gave them 139 patients, well-diagnosed, well-treated. And actually, my clinic was the only site that differentiated Prozac from placebo for relapse prevention. I really gave them their money’s worth.”

Amsterdam was also on industry panels for over a dozen pharmaceutical companies, giving sponsored talks. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that industry representatives began urging him to deviate from his prepared talks. Once he began to experience pressure to “spin” his results in favor of the drug, he said, “I stopped giving talks.”

But he never saw it as systemic corruption. Instead, each time, it looked like one company, or one representative, was under pressure to deliver better results, and so put the pressure on him to tell a better story about the company’s drug. “I was never anti-pharma,” he said. He was happy to take their money, as long as he could continue to deliver accurate data.

Study 352 Comes Calling

In the 1990s, all was going well for Amsterdam. And he thought little about it when, in 1995, Rickels asked if he could help out a junior colleague at Penn, Laszlo Gyulai. Gyulai was involved in a study for GlaxoSmithKline (then SmithKlineBeecham) of paroxetine (Paxil) to see if it would improve depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder who were already taking lithium. According to Amsterdam, Gyulai’s clinic had less than a dozen patients, so it was no surprise that he was struggling to recruit participants for the study. Rickels framed it as a favor—he was embarrassed by Gyulai’s recruitment numbers and wanted Amsterdam’s help.

“I (told Rickels) that I would be willing to be an investigator on the study,” Amsterdam recalled. “I said that I would be willing to recruit patients and help him if I am the co-principal investigator, if my name’s listed as co-principal investigator on the consent form, if Laszlo turns over 80% of the revenue for each patient I recruit. If I end up being one of the principal recruiters in the study, I want to be acknowledged as an author, I want to see the data, I want to co-write the paper.”

Rickels agreed, and soon GSK’s people contacted Amsterdam and helped set up his clinic as the 19th site for the research study. Gyulai had recruited just seven patients over a few years. Amsterdam recruited 12 in just a few months—no surprise again, since his clinic served over a thousand patients.

Amsterdam was deeply involved in the work with those 12 patients, prescribing their medications, checking their dose, giving the assessment measures to see how well the medications were working. Then, just a few months later, the study was cancelled by GSK.

Amsterdam called up his contact at GSK, research director Cornelius Pitts. But Pitts just told him to stop enrolling participants. “I couldn’t get any information about why it came to an end,” Amsterdam said.

Even a year later, when Amsterdam asked Gyulai where the data from that study was, Gyulai told him “we don’t have it yet.” Amsterdam moved on with his life. “It was just one of many projects I was working on.”

The First Hint of Corruption

In 2001, Amsterdam was working on a grant proposal to the NIMH to study fluoxetine (Prozac) as a treatment for bipolar disorder when a member of his research lab mentioned that a study was about to be published in The American Journal of Psychiatry on a similar subject—SSRIs for bipolar disorder—that could provide solid background for the grant-writing process.

Amsterdam hunted down the paper, and quickly realized that some of the listed authors were from his own department at Penn. One was Dwight Evans, chair of psychiatry at Penn. Another was Laszlo Gyulai.

Amsterdam called Evans’ office and requested a copy of the article from his secretary. Soon the fax machine spit out the cover page, which had a handwritten note at the top. “Dear Jay, with compliments. Dwight.”

As Amsterdam read the study, he was overwhelmed by a sense of déjà vu. “I started reading the abstract, and I said to myself, this sounds really familiar. And then I kept reading and I’m thinking—I did this study! And I’m looking and looking, and I can’t find my name. And then I began to get suspicious.”

The lead author on the study was Charles Nemeroff, and while Nemeroff had yet to become publicly identified for his regular participation in ghostwriting exercises, Amsterdam knew that he was part of what many liked to call the “psychiatric mafia,”—psychiatrists that had close ties to industry. So that aroused his questions about the integrity of the article. Even more to the point, he couldn’t understand why Gyulai was listed as an author.

As far as Amsterdam knew, Gyulai had only enrolled a handful of patients, and so he wondered whether Gyulai had somehow overstated his involvement in the study. Had he falsified data, or plagiarized another researcher’s work to do so?

Amsterdam called up his department chair—Dwight Evans—to report his concerns. The university’s policy required that the provost or assistant provost for research be informed that such a concern had been raised and should be investigated. But in this instance, Evans told him that he and Rickels would investigate the matter—no need, apparently, to take this matter to the university higher-ups. Evans asked Amsterdam what he wanted from the investigation.

“I said, ‘I’d like an apology and I want Laszlo Gyulai to be sanctioned for plagiarism,’” Amsterdam told him.

In a letter dated April 3, 2001, Rickels informed Amsterdam of what he had learned from his investigation. Yes, Amsterdam was a co-investigator in the trial, and he had enrolled more patients than Gyulai; and yes a ghostwriting firm, STI, had written two drafts of the paper before it asked Gyulai if he would agree to be the papers’ first author; yes, STI had later replaced Gyulai with Nemeroff as the first author; and yes, there were academic investigators in the trial who had never reviewed or even seen the submitted manuscript.

Although the letter seemed like an admission of scientific fraud, given the evident ghostwriting of the paper, there was no departmental censure of Gyulai. Amsterdam then wrote both Evans and Rickels to express his displeasure. “Am I to assume that it is okay in this department for a junior faculty member to abscond with data from a full professor and publish it without any ramifications?” he asked.

Although Gyulai was never sanctioned, he did send Amsterdam a letter of apology. In it, Gyulai wrote that he understood Amsterdam’s concerns about plagiarism, but stated that he (Gyulai) was the “primary investigator of the Penn site” and did some work on “early drafts” of the article. Gyulai complained that first authorship was “taken away from me” and that he wished that GlaxoSmithKline had allowed Amsterdam to have input on the paper.

At that point, Amsterdam let it go. He wouldn’t revisit the study again until 2010, when his own professional life came under attack.

The Ghostwriting Scandal Becomes Public

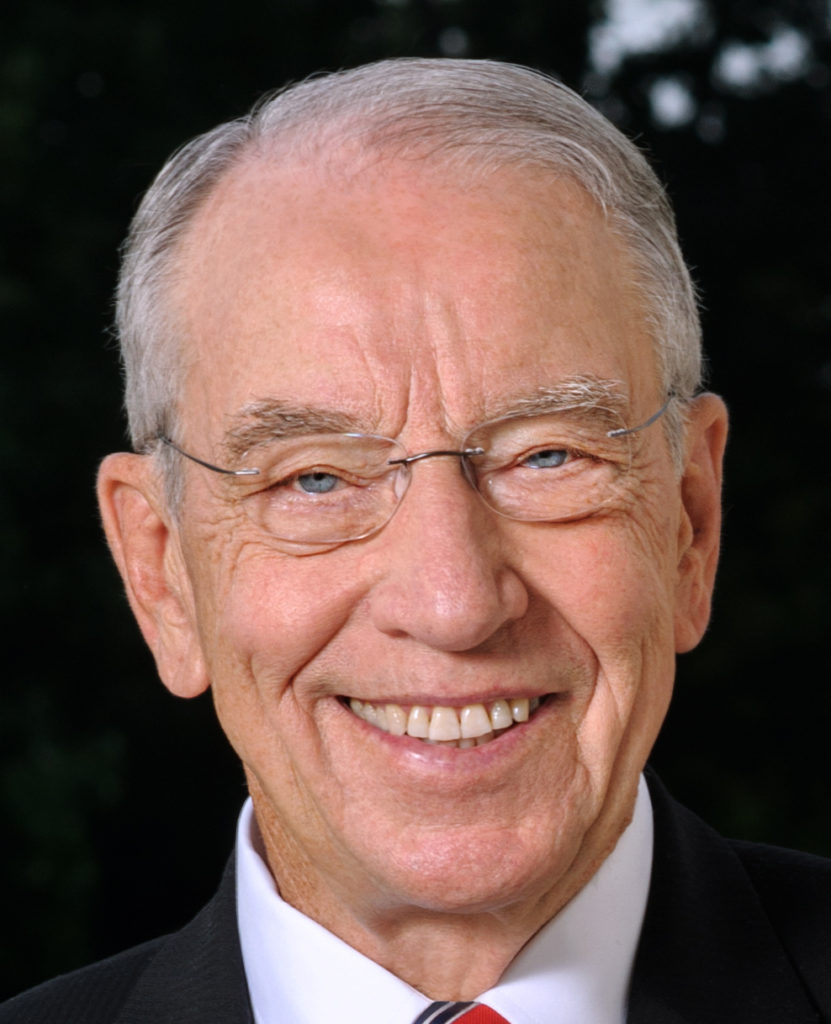

In 2008, Senator Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) of the US Senate Finance Committee began to investigate financial conflicts of interest in scientific research. Paul Thacker, an investigative journalist, was the point man for Grassley’s investigation and his 2010 committee report, which resulted in significant changes to the rules used by academic institutions to define research misconduct.

The picture of corruption that emerged thanks to Grassley’s investigation, and other investigations into industry-funded trials, told of how academic medicine had been horribly corrupted, with psychiatry the specialty that was most compromised.

Pharmaceutical companies would hire ghostwriting firms to manipulate data and write articles “spinning” the results. The drug companies would then get academic psychiatrists, who were described by the companies as “thought leaders,” to agree to be the authors of the study in order to lend credibility to those misleading results. These same “experts” would then be paid to give talks promoting the company’s drug. They would be paid handsomely—in some cases, hundreds of thousands of dollars—to serve the pharmaceutical company’s commercial interests in this way.

Charles Nemeroff—lead “author” on the study 352 paper—became the poster boy for this type of research misconduct. At the time, Nemeroff was an internationally-famous researcher with hundreds of publications and awards. He was chair of the psychiatry department at Emory University.

Grassley’s investigation helped put a dollar amount on this corruption. He reported that Nemeroff was receiving millions of dollars from the pharmaceutical industry, and failing to disclose that pay according to conflict-of-interest rules. As reported in The New York Times, Nemeroff was found in 2008 to have violated federal research ethics rules by hiding $1.2 million, which, if appropriately disclosed, would have prevented him from being the primary investigator on the government grants he was also receiving.

It was business-as-usual for Nemeroff, who’d already weathered two scandals in which he’d promoted new treatments in scientific journals without disclosing in one case that he owned the patent on that treatment or that in the second case that he was being paid by the company behind the treatment.

After yet another investigation, Nemeroff was found to have violated Emory’s policies, and was forced to resign from his position there. But he immediately moved to the University of Miami, where he soon began the process again.

According to Thacker, Nemeroff continued to receive tens of thousands of dollars from various pharmaceutical companies, while also receiving additional government grant money to test their products. In his case, it seemed that there was little financial penalty for violating federal rules and engaging in research misconduct.

Amsterdam Turns Away from Pharma

In the 2000s, Amsterdam was becoming increasingly ill. He was almost completely blind, as he suffered from a severe form of glaucoma, but he was still trying to lecture, conduct research, and see patients. During this time, he conducted research on the class of antidepressants known as MAOIs (monoamine oxidase inhibitors), which have been less utilized due to concern about drug interactions with other antidepressants and certain cold medicines, and dietary restrictions such as alcohol and cheese. However, Amsterdam believes that MAOIs are less dangerous than previously believed.

In 2003, he was working with Somerset Labs to test their MAOIs. He did a trial that showed the drug beat the placebo, and they wanted to publish the results. He began to draft the article, but they suggested he outsource it to a ghostwriting company. They told him they were paying this company $30,000 to write the article, so there was no need for him to do it. But Amsterdam remembered Rickels’ advice: always write your own articles. He wrote the article himself, then sent it to the company.

It was during this time that he began to slowly move away from taking pharmaceutical industry money. He began to drop off the industry panels, as the reps asked him to spin his results more and more when giving talks. This pressure went against his grain as an objective academic.

“I could see that pharma had changed. My respect for it had changed, too,” he says. “I don’t want to do shitty research, which is what the drug company research is now.”

“Science is not the discovery of that new drug. That’s hubris. Science is the replication of that finding, over and over again. I hear colleagues saying ‘we want to show that this drug works.’ I say, ‘no, you want to show that the placebo they’re testing it against doesn’t work.’ And when I started to say that to industry people, they stopped giving me studies.”

By 2006, Amsterdam had had enough. He was done taking pharmaceutical industry money, and funded his research after that entirely with government grant money.

He also began to investigate iatrogenic harms of antidepressants—the notion that the drugs used to treat the condition are, instead, making it more chronic and resistant to future treatment. He began asking questions: Why did those who continued to take the drug long-term have more risk of relapse than those who decided to stop taking the drug? Why did those who tried more drugs have higher risk of relapse?

According to Amsterdam, “People that get repeated antidepressant treatment develop a tolerance to drugs, and, probably as a result of this, we’ve created the field of treatment resistant depression.”

He says that would have been an unthinkable conclusion when he was taking industry money: “The pharmaceutical industry would have shut down that research in every way possible.”

In the Crosshairs of Penn

In the spring of 2010, Amsterdam’s professional life began to fall apart. Later that year, as he struggled to understand why his career at Penn suddenly came under attack—an attack seemingly led by his chairman Dwight Evans—he came to see it as connected to the complaint he’d made nine years earlier about the ghostwriting of study 352.

The first shot was fired on April 6, 2010, when Evans suddenly called Amsterdam and told him to go to the Office of Affirmative Action immediately. “What did I do?” Amsterdam asked. Evans responded by telling him not to “ask questions. Just go there.”

At his meeting with the head of the affirmative action office, Amsterdam was told he was being “investigated” for several complaints made against him. However, the head of the office wouldn’t tell him any details. “You’ll learn in due time,” Amsterdam was told. “I have nothing in writing but you’ll know from the questions you’re asked.”

This was the start of what became something of a Kafkaesque experience for Amsterdam. A flood of complaints were suddenly directed at him, all of them emanating from Evans’ office, and yet he was never formally told of these complaints, or their specifics. Instead, he would be called into the Office of Affirmative Action and questioned about numerous different subjects. Amsterdam inferred from these sessions that the complaints included allegations of retaliation against his staff, racial discrimination, unapproved research activities, photocopying sensitive documents, continuing medical education fraud, and sexual harassment against staff members.

One of the more bizarre episodes occurred on May 13, 2010. Amsterdam was summoned to the affirmative action office by associate director Patrice Miller. As she wrote later that day in an official letter, she “did not find any information to support a finding of sexual harassment.” While Amsterdam may have been glad to hear this, he was also perplexed. This was the first time that he was aware that a complaint of this type had been made.

The most serious complaint made against Amsterdam was that he’d had an “inappropriate relationship” with a female patient. If this complaint were substantiated, he could have lost his license to practice.

Mad in America spoke to that woman. She confirmed every aspect of Amsterdam’s relating of this matter to MIA. She is a professional artist and asked that MIA not use her name.

She first met Jay Amsterdam around 1993, when she became his patient through the clinic. Severely depressed, she was a participant in many clinical trials of different drugs as they attempted to find something that worked for her. Most drugs didn’t, although some worked for a time before their effects wore off. Eventually, after escaping an emotionally abusive relationship and continuing drug trials, she found her mental health becoming more stable. She attributes a lot of her improvement to Amsterdam. “He was such a great doctor,” she said. “He saved my life, you know—finally not being depressed.”

Because she had been in treatment for many years, she remained in contact with Amsterdam, whom she describes as approachable, friendly, and very professional. Amsterdam was a fan of her artwork, and bought some of her paintings.

In 2010, she learned about the allegations against Amsterdam that supposedly involved her. “I was absolutely floored,” she said. “Nauseated, floored. You know, I considered him a dear friend. He saved my life.”

According to both this woman and Amsterdam, the allegation arose from a misrepresentation of some off-the-cuff language he had used in an email to her. Amsterdam had recently purchased one of her paintings, and in the email, he referred to the painting as “booty” (colloquially, to refer to an item of value). The investigative committee pointed to that word as having a sexual connotation, and thus evidence that Amsterdam had an “inappropriate relationship” with this female patient.

“More than anything I felt terrible for Jay and [his wife] Debbie,” she told MIA. “This was ridiculous. It was uncalled for, mean-spirited, fabricated.”

She wanted to sue Penn, but couldn’t find lawyers willing to take on a case like this against the stone wall of Penn’s legal team. “They defamed me,” she said, “and they should have been punished for it.”

Furthermore, during Penn’s investigation of this matter, someone in Evans’ office photocopied and circulated her private medical information to various members of the university administration. This, of course, was a violation of HIPAA laws. “They stole my emails, my health records,” the woman said.

Amsterdam provided Mad in America with documents detailing the history of allegations and complaints made against him, and written records showing that there was an absence of any resolution substantiating the complaints. Even so, the stress of the situation, the sheer volume of complaints, and the feeling that everyone in the university was targeting him for some unknown reason led to a worsening of Amsterdam’s health in 2011. Acting upon his doctor’s advice, he took a medical leave.

Blowing the Whistle

Once on leave, Amsterdam struggled to figure out why his professional life had suddenly collapsed around him. Although he was now unable to see, his wife Debbie helped him search the internet for information about Penn and Evans. One day, she found an article about a court case in Philadelphia that led him into a larger dive into Evans’ involvement in the ghostwriting scandal.

In this case, a child had been born with a congenital heart defect after the mother used paroxetine while pregnant. The family sued GSK, accusing the company of hiding data about the harms of the drug. GSK lost the case, and ended up paying a $2.5 million penalty.

GSK, it seemed, had engaged in research misconduct. That article led Amsterdam and his wife to other articles citing UK psychiatrist David Healy, who had testified against GSK in the trial. In one article, Healy named several academic researchers who were on pharmaceutical executives’ “speed-dial” lists. One name immediately jumped out to Amsterdam as soon as his wife read it aloud: Dwight Evans.

Now, for Amsterdam, the light bulb was starting to turn on.

In the spring of 2010, when Amsterdam had been hit by the first complaint, Senator Charles Grassley was readying the release of his report on medical ghostwriting. In that report, which was released on June 24, 2010, Grassley noted that during his investigation he had asked Penn Medical School about its policies on ghostwriting, and Penn had informed Grassley that it had “policies against plagiarism and it considered [ghostwriting] to be the equivalent of plagiarism.”

This inquiry from Grassley surely would have raised anxiety in Penn’s psychiatry department. Not only had Amsterdam charged Gyulai with stealing his data, but Evans was also listed as an author of the Study 352 report, and yet Rickels, in a letter to Amsterdam, had told of how the paper had been ghostwritten by STI.

Moreover, as Evans likely knew in the spring of 2010, Grassley and his lead investigator, Paul Thacker, already had their sights set on him related to another instance of his “authoring” a ghostwritten paper. This instance of ghostwriting became public that fall, when Thacker, in a letter to NIH director to Francis Collins, told of how Evans had signed off on an editorial written by Scientific Therapeutics Information (STI), with the ghostwriting firm billing GlaxoSmithKline for its services.

Thacker wrote:

“According to the documents, Sally Laden of STI wrote an editorial for Biological Psychiatry in 2003 for Drs. Dwight Evans, Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, and Dennis Charney, then an employee at the NIH and now Dean of Research at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine at New York University.

“In an email to a GSK employee, Ms. Laden wrote, ‘Is there a problem with my invoice for writing Dwight Evans’ editorial for the [Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance]’s comorbidity issue to Biological Psychiatry?’ Yet, when published, the ‘authors’ Evans and Charney only stated, ‘We acknowledge Sally K. Laden for editorial support.’”

In his letter, Thacker urged Collins to approve new policies that would recognize ghostwriting and plagiarism as research misconduct. He encouraged Collins to consider “enforcement mechanisms such as disciplinary action and dismissal” for the researchers involved.

Evans was now on the hot seat. Thacker’s complaint to Collins told of plagiarism for hire. Yet, Penn, in response to Thacker’s new revelation, took no action against Evans. As Thacker said in a subsequent article published a few months later, Penn just “blew it off” as though it were a matter of no account.

Thacker, in his latest article, publicly named Evans and Penn as an example of the corruption in academic medicine that needed to be cleaned up. “Students should really be pissed off that professors get away with this type of fraud when students receive steep penalties,” he wrote. “What makes this all even more bizarre and insulting is that Dr. Evans is on the board of Penn’s Scattergood Program for the Applied Ethics of Behavioral Healthcare, a program dedicated to healthcare ethics.”

Once Amsterdam learned of Thacker’s articles, he could put together a timeline that provided a likely explanation for why he had been hit with all those complaints in the spring of 2010. All of those complaints had emanated from Evans’ office, at a moment when Evans had reason to be worried about Grassley’s investigation of ghostwriting, and if Thacker continued his digging, he might stumble upon the very study—study 352—that Amsterdam had complained about in 2001. And that—or so it would seem—would mean big problems for Penn and Evans.

“I think what happened is that Evans got all wigged out,” Amsterdam said. “He remembered the fact that he plagiarized, in 2001, an article in The American Journal of Psychiatry. And he knew that I knew, and that I knew he swept it under the rug by not taking it to the university, with his crony, Rickels. And he knew that if I were called to testify before Congress, I would tell them what happened.”

Amsterdam didn’t wait for Grassley’s call. On July 8, 2011, he filed a whistleblower complaint with the federal Office of Research Integrity (ORI) alleging that Evans and the other authors had committed plagiarism by placing their names on that ghostwritten paper published in 2001.

Penn’s Response

Given Rickels’ 2001 letter to Amsterdam, which confessed that STI had written the initial drafts of the article, and that many academic investigators in the trial hadn’t reviewed or seen the submitted article, it seemed that Penn would need to censure Evans. The ghostwriting element was clear. Even Gyulai had stated in his letter of apology that the ghostwriting firm had “given” first authorship to Nemeroff, and Penn had told Grassley that it considered agreeing to author a ghostwritten article to be a form of plagiarism.

But Penn just dismissed Amsterdam’s complaint with a wave of its institutional hand.

In a letter to Amsterdam dated December 5, 2011, the university admitted that the two researchers had published ghostwritten articles, and while it noted that the ghostwriting firm’s authors should have been listed on the publications, it decided that there had been no misconduct because Penn, at that time, did not have a formal policy prohibiting faculty and researchers from appending their names to ghostwritten work.

In its statement to the press, the university was even more adamant. A Science article published on March 2, 2012 had this headline: “Penn Clears Two Faculty Psychiatrists of Research Misconduct Charges.”

There was, the university stated in its press release, “no plagiarism and no merit to the allegations of research conduct” because Gyulai and Evans had helped conduct the research and analyze the results and “contributed to the paper,” which had “presented the research findings accurately.” As for Amsterdam, the university stated, he should not have been listed as a co-author or in the acknowledgements, because “his role did not meet the journal’s guidelines for authorship.”

The university’s response to Amsterdam’s whistleblowing did not impress Thacker and the leaders of the Project on Government Oversight. POGO sent a letter to the office of the President of the United States stating that the president of Penn, Amy Gutmann, had ignored the evidence against Evans. “They just blew it off,” Thacker wrote.

At that time, Gutmann was the chair of Obama’s Bioethics Commission, and Thacker asked how she could be expected to function capably in that position, given this brush-off. “Dr. Gutmann’s bona fides on bioethics—to borrow a phrase from Penn’s own spokesperson—appear to be ‘unfounded.’”

Deconstructing 352

After filing his complaint with the federal office of Research Integrity, Amsterdam teamed up with bioethicist Leemon McHenry to write a peer-reviewed article about the 2001 paper. They looked at the way the data from study 352 had been analyzed, and then how it was presented in the article itself. Their article was published in 2012 in the International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. In it, Amsterdam and McHenry wrote that they “show how primary and secondary outcome analyses were conflated, turning a ‘negative’ clinical trial into a ‘positive’ study—with conclusions and recommendations that could adversely affect patient health.”

The study, they wrote, was designed to test GSK’s drug, paroxetine (Paxil) against both an older antidepressant, imipramine, and a placebo control. The participants were people with a bipolar disorder diagnosis who were taking a full dose of lithium, but not responding to lithium treatment. The goal was to see if Paxil could improve depression when lithium wasn’t working.

However, the study was plagued with problems from the start. The researchers struggled to enroll enough participants (hence the recruitment of Amsterdam, to gain access to his prestigious bipolar disorders clinic). Even with Amsterdam’s help, the researchers didn’t enroll enough participants to meet the original requirement.

Still, GSK continued the study. Each of the 117 participants was randomly assigned to one of three groups: Paxil, imipramine, or placebo. The original test was to see how the groups did, on average, on both the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD, a common measure of depression severity), and the Clinical Global Impression Severity scale (CGI/S, a subjective, 7-point scale of how “ill” a clinician considers their patient).

The researchers also used the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) to assess whether Paxil caused manic or hypomanic episodes—a well-known harmful side effect of SSRIs.

However, the results showed no beneficial effect for either Paxil or imipramine. Improvement was no better than placebo on any of the scales used.

This was a failed study. But rather than publish that finding, GSK’s ghostwriters looked for other ways to put a positive spin on the study. Finally, a statistician working for GSK hit on an idea that might produce a positive results—splitting the participants into two groups, one on high doses of lithium, and one on low doses of lithium.

This was a post-hoc analysis (conducted after the study was over), so the researchers couldn’t actually randomize participants to receive a specific dose. Moreover, all the participants were stabilized on a dose that was considered within the normal range. Nonetheless, the statistician arbitrarily separated those with a slightly higher dose from those with a slightly lower dose.

However, even then, the statistician couldn’t find an effect when looking at how many people experienced a “response” to the drugs. “Response” in this case was defined as having a HDRS score of ≤ 7, or a CGI/S score of ≤ 2. Neither Paxil nor imipramine were significantly better than placebo and that was true for both the “high-lithium” and the “low lithium” group.

However, GSK’s statistician still had one more data-mining exercise to try. The average change on the HDRS and the CGI/S scales for both Paxil and imipramine was greater than for placebo, and this difference was “statistically significant.”

Although the published report of Study 352 did note that no “statistically significant differences in response rates were seen among those receiving paroxetine, imipramine, or placebo,” it was the “average change” on the two scales that was featured in the abstract of the article, which was used to support this bottom-line conclusion: “Antidepressant therapy may be beneficial for patients who cannot tolerate high serum lithium levels or who have symptoms that are refractory to the antidepressant effects of lithium.”

This post-hoc data mining is known to be unethical, and if presented as a bottom-line finding, a type of research fraud. The joke within research circles is that if you “torture” the data long enough you can always find the result you want, and it was that process of data manipulation that Amsterdam and McHenry documented in their analysis of the study.

There were other research sins to be found in the published article. For instance, the researchers didn’t report the YMRS data that was used to assess the risk of drug-induced mania/hypomania, which is a scientific sin of omission, one that in company-sponsored trials was regularly used to hide adverse effects of the sponsor’s drug.

After Amsterdam and McHenry published their deconstruction of study 352, they spearheaded a campaign to get the study retracted. They sent a letter, signed by 18 researchers, to the editor at the American Journal of Psychiatry, which had published the study 352 paper. They enumerated the evidence: that the study was ghostwritten, that the results were misleading, and that further information about the misconduct was still coming out through litigation.

They never received a response.

The Second Deconstruction of 352

The involvement of Scientific Therapeutics Information (STI) as the ghostwriting firm hired by GSK in study 352 became known as the result of an ongoing lawsuit, Burdick vs. GSK. That lawsuit has led to a cache of internal memos, emails, and letters between GSK, STI, and the “authors” of the article becoming publicly available.

With access to these documents, Amsterdam and Leemon McHenry teamed up once again to write another article about study 352, published in November of 2019 in the Journal of Scientific Practice and Integrity. The documents shed further light on the ghostwriting process—and corruption in the publication process at the American Journal of Psychiatry—that allowed study 352 to enter the medical literature despite its evident spinning of results.

The Ghostwriting

The entire manuscript of study 352 was written by Sally Laden, Grace Johnson (another editor at STI), and possibly Laden’s boss, John Romankiewicz (it’s unclear if he did any of the actual writing, or simply signed off on Laden’s work). The first draft was completed before the listed academic authors were even contacted.

A letter dated April 4, 1997, from Johnson to Muriel Young (the GSK contact for the project), enclosed the second draft of the manuscript. Johnson wrote that she would be working with the internal GSK authors (Gergel, Pitts, and Oakes) until they approved the manuscript. Then, Johnson would begin contacting the authors whose names they wanted to appear as authors of the study.

At that point, the proposed study authors were Gyulai and Gary Sachs. Neither Nemeroff nor Evans were being considered as study authors at that time.

Johnson wrote to Young: “The manuscript has been modified based on your comments and those of Ivan Gergel, Cornelius Pitts, and Rosemary Oakes. […] We will contact the named authors (e.g. Laszlo Gyulai and Gary Sachs) once we receive your approval.”

Although Nemeroff and Evans later told journalists that they wrote the entire study 352 manuscript themselves, without any assistance from STI other than “proofreading” help, Johnson’s letter makes it clear that Nemeroff and Evans did not see the manuscript until at least the second draft was complete.

A month after Johnson informed GSK’s Young that the second draft was complete, Johnson, who identified herself as an editor at STI (i.e. identified herself as an editor at a ghostwriting firm) sent the following letter on May 20, 1997. One went to Evans, and an identical one went to Nemeroff.

letter2

The letter couldn’t have been more blunt. The second draft of the manuscript was finished, and Nemeroff and Evans were “invited to participate” as authors of the article. Or to put it another way, they were being invited to commit research fraud.

Next, in a June 6, 1997 letter, Johnson told GSK that Nemeroff and Evans were on board, and would be listed as authors. She wrote:

“[Draft II] was sent to SB [GSK] and Drs. Gyulai and Sachs on April 4, 1997. SB added to [sic] more authors (Dr. Nemeroff and Evans) on May 20, 1997. To date, we have received comments from Dr. Young, Neil Pitts, and William Bushnell. Dr. Gyulai requested SB to complete additional statistical analysis on the data.”

Nemeroff would become first author on the paper. And when Amsterdam read these letters, he realized that the only investigator in the trials who saw most of the drafts, and was at least slightly involved in analyzing the results, was Gyulai. In 2001, Amsterdam had thought that Gyulai might have been the principal culprit in claiming authorship for work that he had not done, but it was now clear that Nemeroff and Evans were much worse offenders.

Publication Corruption

As Amsterdam and McHenry had documented in their 2012 deconstruction of study 352, the conclusion drawn in the abstract had come through a data-mining exercise, which would be evident to any reviewer of the submitted article. And yet it was published in the American Journal of Psychiatry (AJP), a high-profile journal in the field.

The cache of documents from the lawsuit details how this came about.

Peer reviewers of the submitted article recommended against publishing it, and this remained so even after several “revise and resubmit” processes. In a June 12, 2000 email, a deputy editor at AJP, Jack Gorman, who like Nemeroff was a paid consultant to GSK, wrote Nemeroff to detail what further revisions were needed to get it accepted at AJP.

“The statistical reviewer [of the paper] adamantly recommends rejection,” Gorman confessed. “The paper,” he added, “still has a very biased tinge to it,” and with all of the public scrutiny over journals publishing biased drug company studies, there was “no way [AJP executive editor Nancy Andreasen] would allow it [to be published] in its present state.” Moreover, he noted that the “study just doesn’t support much in the way of a claim that paroxetine worked particularly well here compared to other interventions.”

In other words, it was clear that this was a failed study. But Gorman then laid out a plan for STI to add in some admissions of failure, and if so, then it could hopefully be published in AJP, for this was “a great study,” he told Nemeroff.

Later that day, Nemeroff wrote Laden to inform her of Gorman’s feedback. Although further revisions were being asked for, Nemeroff assured Laden that Gorman wanted to see it published in AJP. “Jack is clearly willing to fight for the paper,” he wrote, adding that STI should, in the revision, try to “tone down the perceived commercial bias so Jack can pull it over the line.”

And if it didn’t get accepted, GSK needn’t worry. “We can publish it relatively quickly in Depression and Anxiety,” Nemeroff told Laden.

Laden then passed along this message to GSK. Nemeroff wanted to “try one more time” to get it published in AJP, she told GSK, and if not, “the paper will be accepted by Depression and Anxiety.”

In sum, the paid consultants to GSK—Nemeroff and Gorman—were coordinating their efforts to get the study published in AJP, even though it was evident to all that paroxetine hadn’t proven to be superior to placebo or the other interventions. And if AJP didn’t pubish it, then they could always publish it in a different journal without any worry that it might be rejected there too.

And so the wheels of revision and resubmission spun on, and in January 2001, the study was accepted for publication in AJP, with a conclusion in the abstract that told of how paroxetine could be beneficial for treating bipolar depression, at least in certain groups of patients.

The Spoils of Corruption

The academic psychiatrists in this story—those involved in this corruption—did not see their careers suffer in any significant way.

Charlie Nemeroff is currently the acting chair of psychiatry at the University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School. According to his bio there, “He is a member of the [American Psychiatric Associaton’s] Council on Research and Chairs both the APA Research Colloquium for Young Investigators and the APA Work Group on Biomarkers and Novel Treatments.”

In other words, he’s a mentor for young researchers, and he’s one of the people in charge of the American Psychiatric Association’s policy on research ethics. The website doesn’t mention that he was repeatedly sanctioned for unethical research conduct at his university and by the federal government.

In 2009, Dwight Evans became president of the American College of Psychiatrists. He still teaches and does research at Penn. He ended his tenure as chair of the psychiatry department on January 1, 2017.

Laszlo Gyulai is the director of the Bipolar Disorders Unit at Penn Medicine, and still teaches and does research at Penn.

Jack Gorman, onetime deputy editor of The American Journal of Psychiatry, was a star on the rise in 2001. In 2006, he became president of McLean Hospital in Belmont, MA—one of the premiere psychiatric hospitals in the country. But then he experienced a precipitous fall. Four months after taking the job, he resigned and lost his license to practice psychiatry. A year later, The Boston Globe reported on why: he had sex with a patient, on more than one occasion.

Nonetheless, Gorman has made a bit of a comeback as a science activist, with no mention of his loss of license in the press tour. He recently co-wrote (with his daughter) a book titled Denying to the Grave. It purports to examine why people ignore scientific facts.

STI no longer exists, but Sally Laden is now a freelance medical writer. She’s also an editor for the scientific journal Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy.

Jay Amsterdam continues to write and conduct research, even while blind and on medical leave from Penn. His recent work focuses on how antidepressants may increase the chronicity of mood disorders, turning a once-episodic, recoverable depression into a treatment-resistant, lifelong condition.

Amsterdam’s far more cynical now about the research he used to conduct. He finds it difficult to believe he used to work hand-in-hand with the pharmaceutical industry. But, he says, it was a different time. The industry changed, and academia changed. No more was academia the place of learning, of objective science. It had become a competitive, dishonest, and corrupt world.

“I sometimes look back now. I mean, this has been a really rocky 10 years for me, from an emotional point of view. But I say to myself, would I really want to be back there, competing with these people who are not really honest? They’re so competitive, untrusting. No one helps each other in academia anymore. People taking advantage of a blind guy! Would I really want to be back there? No.”

As of this writing, the ghostwritten 2001 article, with its misleading conclusions about the data in study 352, remains a part of the research literature. It hasn’t been retracted, or even corrected, by The American Journal of Psychiatry.

After its publication in 2001, the article was cited in hundeds of medical journals, textbooks and practice guidelines as evidence that Paxil could be beneficial in the treatment of bipolar depression. It may still be cited for that “finding,” and in that way, the corruption lives on.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

Thanks for this article. Sheds much light on something I knew little about. It’s no wonder Dr McHenry Contacted me in 2019 about something I wrote disagreeing with him. He let me know the industry was still doing everything it could to attack those who would throw back the veil. It’s obvious they are still doing it. And with some impunity

Report comment

Wow Peter, I’m amazed at the research you put into your articles.

Well done.

Although Jay only seemed to question the harms of psych drugs in 2006, after having been in the biz of “treatment” since 1975.

Report comment

And if only we could get the public’s/society’s attention to this matter…

Report comment

JeffreyC, I think quite a few read

Report comment

As someone that’s consumed strong Psychiatric Drugs over a period of time (and recovered as a result of discontinuation), I’d say that that the overall mental and physical damage done by the drugs is worse than the “conditions” the drugs are supposed to treat.

“….He also began to investigate iatrogenic harms of antidepressants—the notion that the drugs used to treat the condition are, instead, making it more chronic and resistant to future treatment. He began asking questions: Why did those who continued to take the drug long-term have more risk of relapse than those who decided to stop taking the drug? Why did those who tried more drugs have higher risk of relapse?..”

Report comment

How can people like Charles Nemeroff get away with their “behaviour” (in Mental Health). If this was to happen in any other area surely they’d be prosecuted.

The “Mental Health” corruption has got to go higher than doctors and drug companies!

Report comment

yes Fiachra,

What “personality disorders” lurk within the system?

Manipulation, coercions, controlling…..

I think they generally try to control their “behaviours”, but to push drugs forward, there are always going to be lies and corruption.

None of these people hold a job of honour.

“daddy, what do you do at your job?”

“I give drugs to people who are sick”

“daddy, what is wrong with them?”

“Would you like to go to Disneyworld?

Report comment

“The “Mental Health” corruption has got to go higher than doctors and drug companies!”

A quick look at the ‘shareholders’ and which of them is in a position to influence outcomes of investigations might give a clue. Authorities with a duty to act commiting acts of strategic negligence to ensure that no action is taken (which in my country is done to ensure that people know nothing will be done so they stop trying) Because it would seem someone has been ensuring this house of cards is kept standing despite knowing that the frauds have been at work and that people are being harmed as a result.

Good work Peter.

Report comment

We have insight into the conflict of interest fraud that brought Risperidone to market via Dr David Rothman. I’m wondering if there is any information on how the two other popular prescribed ‘antipsychotic’ major tranquilizers… Qlanzapine and Quetiapine came to market ?

Report comment

“In trials, Caplyta did not cause akathisia, a feeling of jitteriness among patients, which is extraordinarily uncomfortable and makes people “jump out of their skin”, the company said.”

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/reuters/article-7821711/FDA-approves-Intra-Cellullars-schizophrenia-treatment-shares-soar.html

The Company said….so it must be true everybody.

Report comment

“… the corruption lives on.” That’s what happens when a society does not arrest and convict, or sanction, etc. criminals. Truly, the psychologists and psychiatrists are amongst the most corrupted and criminal people on this planet. For goodness sakes they are running a primarily, systemic child abuse and rape covering up, and profiteering business, by DSM design.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

But the same is true for other “professions,” many within which who do also deserve to be arrested, but aren’t. Which is why we’re now at this point:

“We now live in a nation where doctors destroy health, lawyers destroy justice, universities destroy knowledge, governments destroy freedom, the press destroys information, religion destroys morals, and our banks destroy the economy.”

It’s a shame so many within those professions corrupted themselves, because their greed is destroying America, for all of us. And as a banker’s daughter, who was internally screaming “Greenspan spanned the green to the point it’s ‘irrelevant to reality'” long ago. I know the wrong people took control of this country long ago, and that paper money you worship is worthless.

Report comment

Peter, I am grateful to you for penning this fabulous report. Seriously, this is an outstanding piece! It should be read far and wide. Imagine if basically the entire clinical trials literature on the modern generation of psychiatric drugs (i.e., since Prozac, if not before) is corrupted in the same way? I have no trouble believing that Study 352 and 329 are not exceptions but representative examples of a literature so hopelessly corrupted that it’s findings have no truth value whatsoever. And of course, this literature is the source for “clinical practice guidelines” and “evidence-based practice” in medicine. Most clients I see have been unwitting victims of such practices from doctors who have no idea about the issues you raised. The scope and ramifications are truly mind-blowing. Thank you for what you do. And please keep up your great work.

Report comment

Yes it is very good indeed.

“Imagine if basically the entire clinical trials literature on the modern generation of psychiatric drugs (i.e., since Prozac, if not before) is corrupted in the same way?”

The people who were/are on the wrong end of it didn’t/don’t imagine. We know it’s all crap causing mass destruction for finacial gain and to sate the need to inflict pain/akathisia by psychiatrists. And if those outside of all this do not believe me, I invite you to take just one dose of a ‘antipsychotic’. Then think of those who are forced to go through that, even people with anxiety can be/ARE forced to do it every day.

Report comment

1 in 4 women are on antidepressants. 1 in 5 women is in an abusive relationship at any given time. What do y’all think the overlap is there? It’s gotta be huge. Has this question ever even been asked?

Report comment

I was in therapy for 20 years and had about 4 episodes of depression during that time. No one ever mentioned emotional /verbal abuse as a possible cause of the depression. According to what I’ve read in a few places, most of the field of psych workers didn’t recognize verbal abuse as an actual entity until about 1994. I divorced in 2000 and haven’t had an episode of depression since, despite losing both parents, changing jobs, and navigating relationships. Depression always happens for a reason and once you can address its roots, you can find a way out of the darkness.

Report comment

Well said! There is no excuse for any “professional” not asking every client about relationships and family history. It seems today that such professionals are the exception rather than the rule.

Report comment

Never ask a question unless you know what the answer is.

I got asked about relationships and family history by a ‘professional’, trouble was it didn’t suit the false narrative he was fabricating in his documents. He needed me to be the violent one and the family who had threatened me, attempted to plunge a knife into my chest whilst I was laying on a couch, and then drugged me with benzos without my knowledge to enable a weapon to be planted on me for police to provide a referral for this ‘professional’.

So he ‘verballed’ it up. He “observed” me having thoughts of harming others (which funnily enough happened three weeks before he used police to jump me in my bed after I had collapsed from the spiking). He “observed” that I refused to answer re substance abuse, which is funny really coz he knew I had been spiked with benzos and I didn’t. Still, i’m sure he knew that by slandering me as a wife beater I would be treated very differently than if he had told the truth on his sworn statutory declaration.

Verbal abuse, is that what is done by these ‘mental health professionals’ when they slander your character and produce fraudulent documents making false claims about illnesses that don’t exist? Certainly the use of ‘verballing’ is an abusive and known corrupt practice that has a significant effect in cases of wrongful convictions. But it is viewed by some who like to disregard the law as being a “noble” form of corruption. Until they become the victims of it of course.

Plenty of folk round here know all about verbal abuse, though some like to think of it as ‘medicine’.

Report comment

Dear Peter,

Thank you for writing such a clear exposition and vitally important account of scientific fraud. The scale of harm resulting from this fraud like this is now being revealed as lives, like mine, are ruined by drugs like Paroxetine.

Thank you for writing this and for showing that scientific narrative is as important as any other form of evidence.

I am about to retire as an NHS psychiatrist who has worked in Scotland for over 25 years. I have petitioned the Scottish Parliament to introduce Sunshine legislation:

https://www.parliament.scot/GettingInvolved/Petitions/sunshineact

Outside of Medicine I make short films. Over 6 years ago I made this film about Charles Nemeroff:

https://vimeo.com/68299094

Peter, might it be possible to make a short film based on this, your Mad in America report? I would understand if this is not possibel. You can contact me at:

[email protected]

kind wishes,

Dr Peter J Gordon

Bridge of Allan,

Scotland

Report comment

Thanks, Peter, for your wonderful work on this article. As I was reading it, I kept thinking “How can we ever trust any drugs?” The corruption is good to know about, but as ordinary consumers who may need medication, what actions can we take? I remember hearing one researcher say to never take a drug that’s been out less than 5 years…..Any other ideas? Thank goodness for people like Amsterdam.

Report comment

And the same guys who did these alleged studies would roar with fury at the thought of using B1 and/or B12 as a treatment for depressions, preferring treatments they’d falsely proved to be effective, despite also knowing they’d scammed the results of their alleged studies.

Report comment

In the late ’70s the national mental patients liberation movement coordinated a boycott of SmithKline’s over-the-counter products (including Contac Cold Capsules and Sea & Ski products) due to their production and promotion of Thorazine, Stelazine and Prolixin. Once we have a new anti-psychiatry survivor network in place perhaps we should resume this campaign.

Report comment

Excellent article, though it could be shorter. The authenticity of “pharmaceutical company research” in such journals as JAMA and New England Journal of Medicine cannot be trusted for many decades now, due to the ghostwriting that most companies employ. It is beyond disgraceful that these articles actually have been published. I know this was the case about 10 years ago, while I was still a mental health advocate; I’m not sure that it has changed for the better. But the fact that it even occurred makes you wonder…if you cannot trust JAMA & NEJM, what can you trust as a researcher?

Report comment

2004 FDA meeting on Paroxetine

“Dr Laughren (for FDA) your daughters and my daughters were in the same school, one of your daughters was in the same class as my daughter. My daughter was given Zoloft (Paroxetine, paxil Seroxat) at the age of 12 because she was anxious about going to school, you know she had school refusal. Candace was put on Zoloft and a week later committed suicide. And Tom Laughren knew that these drugs…. Candace’s mother became aware that he knew that these drugs could do this.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZrYPYlXA0b4&feature=youtu.be&t=1887

Now I know what many of you think about DH re ECT but his work on Akathisia/Toxic Psychosis is very important.

Report comment

Do not stop researching and writing. I am reading in a great deal of pain. I began “treatment” in 1980 for chronic depression and “mood swings” (emotional dysregelation possibly due to genetic emotional sensitivity but in conjunction with prolonged psychological and social violence). I threw myself into the European/American System in Los Angeles for help.

Peer reviewed research is saving me. It is attended by an unwavering flood of education and personal experience of survivors of the initial trauma of oppression in addition to the overwhelm of “treatment resistant” results provided by the “education” of old boys.

This is probably old hat to you; these articles are a beginning for me. But I seem to be dying young now. I intend to live another forty years, but the medical establishment is saying not; the damage is done. They are saying I did it. Own it. I am not.

Please write on. I began worship of professors and doctors before the decade when CBT, statistics and studies had the funding to become ineffective in their little boxes, and irrelevant. They have not destroyed my life, but have caused a suffering that was never necessary in its completeness. This eugenic education has caused the suicides of George Foster, Catherine Foster, Frank Foster, Opal Antonito, Ernie Curly, Devin Lange and Stewart Lupton.

They are keeping the people I “grew up” with in a CMHC without families, independent income or positive career choices. I struggle to even believe in God anymore. But I do. Have met Them. They are diligent, and kind, like you. Don’t ever stop.

Report comment