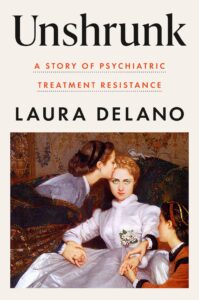

On March 18, Viking Press published Laura Delano’s memoir: Unshrunk: A Story of Psychiatric Treatment Resistance. While a number of writers have published memoirs telling of harm that stemmed from a psychiatric diagnosis and treatment with psychiatric drugs, this is a book, precisely because it is being published by a major publisher, that appears certain to gain major media attention, which has been lacking for other memoirs that told of harm. Indeed, on the day the book was published, The New York Times published a lengthy story about Laura Delano and her husband Cooper’s work to provide support, through their Inner Compass Initiative, to people seeking to taper from psychiatric medications.

As can be seen in the book’s title, Laura is placing her story solidly within a larger societal context, telling of a paradigm of care that not only did her great harm, but has done much harm to so many. As such, she is not telling a story of misdiagnosis, or of overmedication, but of harm done while being treated by the “best psychiatrists” in the country.

As can be seen in the book’s title, Laura is placing her story solidly within a larger societal context, telling of a paradigm of care that not only did her great harm, but has done much harm to so many. As such, she is not telling a story of misdiagnosis, or of overmedication, but of harm done while being treated by the “best psychiatrists” in the country.

For that reason, it is going to be instructive to see how the mainstream media treats her story. As pre-publication reviews have said, her book is very well written and a compelling read. As such it could serve as a pivotal moment in our larger societal narrative about the merits of our disease model of psychiatric care. Is it doing more harm than good? That is the question that arises from her personal story, and if the mainstream media addresses that question in its reviews of Unshrunk, then our larger societal discussion could pivot in a new direction.

The New York Times article was the first to weigh in on the topic. Moreover, both The New York Times and The Washington Post have now published reviews of the book, and so there is the start of a mainstream media response to review.

The Clash of Narratives

In Unshrunk, Laura tells of how when she read my book Anatomy of an Epidemic, she suddenly saw her past life as a mental patient in a new light. Perhaps it wasn’t that she suffered from a mental illness, but rather it was her diagnosis and drug treatment that had caused her such suffering. Laura contacted me via email, we met in a café, and she became the first person to tell her personal story on what was, at that time, my personal blogging site (madinamerica.com). Soon after that, madinamerica.com transformed into a web magazine, with Laura regularly blogging for us and also working for several years as an editor overseeing the publication of personal stories.

Now, Anatomy of an Epidemic and the Mad in America website tell of how our society organized its thinking around what can be best described as a “false narrative of science.” The book and website tell of a counter-narrative to the conventional narrative that mainstream media present to the public.

The story of the conventional narrative dates back to 1980. That year, the American Psychiatric Association adopted a disease model for categorizing and treating psychiatric disorders when it published the third edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). The public soon began to hear about how major psychiatric disorders were caused by chemical imbalances in the brain, and that a second generation of psychiatric drugs, starting with the introduction of Prozac in 1988, fixed those chemical imbalances, much like insulin for diabetes.

Together, psychiatry and the pharmaceutical industry successfully promoted this narrative to the public, leading to a great expansion of the psychiatric enterprise. There was a dramatic increase in the number of people diagnosed, including the diagnosing of children, and a dramatic increase in the prescribing of psychiatric drugs.

Anatomy of an Epidemic provided readers with a counter-narrative to that narrative of progress. As a starting point, it detailed how the number of people receiving disability payments due to psychiatric disorders soared from 1987 to 2007, which would not be expected to happen if a medical discipline has developed drugs that are an antidote to a “disease.” And so I raised a question: what did the research literature tell about the long-term impact of psychiatric drugs?

As a start to that inquiry, I told of how investigations into the chemical imbalance theory of mental disorders had failed to find such imbalances in patients prior to their being medicated. Instead, the investigations had revealed that the drugs, over the longer term, induced the very chemical abnormalities hypothesized to cause the disorders in the first place.

I then set forth what research revealed about the long-term impact of these drugs. I traced the relevant research from the moment the first generation of psychiatric drugs were introduced, and for each major class of psychiatric drugs there is a trail of evidence that leads to the conclusion, as surprising as it may be, that the medications worsen long-term outcomes. While many people on medications may do fine, aggregate recovery rates are lower than for those off medication long term.

In the last third of the book, I detailed the guild and financial forces that led to the public being told a “false narrative” of great scientific progress.

As could be expected, this book provoked a hostile response from many in American psychiatry, a hostility that was apparent in several book reviews published by psychiatrists in psychiatric journals. In addition, given that the narrative in Anatomy of an Epidemic countered the conventional disease-model narrative that the mainstream media had embraced, the mainstream media were primed to similarly dismiss the book. The media mostly responded by ignoring the book, and if on a rare occasion a major media outlet was prompted to write about it (or Mad in America), it often did so with a few words of dismissive criticism.

Thus, Laura’s book, precisely because she places her story within that counter-narrative, presents a challenge to the media as they review her book. Will the book prompt reviews and articles that lend legitimacy and credibility to that counter-narrative? Or will the reviews and articles that appear in the mainstream media discount the element of her story that tells of a paradigm of care that is, for so many, harmful? And since Anatomy of an Epidemic does play a significant role in Laura’s story, as it provided her with the counter-narrative that changed her understanding of her past, how will reviews treat this book?

The March 18 article in The New York Times provides the first example of a response to this question.

The NY Times: We Stand by Our Story

Although Laura’s book was just published, The New Yorker published a lengthy article on Laura in 2019, and the author Rachel Aviv navigated this potential minefield of clashing narratives in something of a moderate way. She wrote this about Anatomy of an Epidemic:

“The book tries to make sense of the fact that, as psychopharmacology has become more sophisticated and accessible, the number of Americans disabled by mental illness has risen. Whitaker argues that psychiatric medications, taken in heavy doses over the course of a lifetime, may be turning some episodic disorders into chronic disabilities. (The book has been praised for presenting a hypothesis of potential importance, and criticized for overstating evidence and adopting a crusading tone.)”

The New York Times, in its March 18 article, was not so moderate. It took time out from telling Laura’s story to write this about Anatomy of an Epidemic:

“At 27, she picked up a book by the journalist Robert Whitaker, Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America. In the book, Mr. Whitaker proposed that the increasing use of psychotropic medications was to blame for the rise in psychiatric disorders. In scientific journals, reviewers dismissed Mr. Whitaker’s analysis as polemical, cherry-picking data to support a broad, oversimplified argument.

As can be seen, the article is informing readers that “science had spoken,” and the verdict was in. In science journals, reviewers had documented that I had “cherry-picked” data to support my “argument,” and these scientific reviews had collectively shown that the book should be “dismissed.” Case closed.

After reading the story, I wrote the author of the article, Ellen Barry, to ask what were her sources for that statement. She replied there were three reviews that she had relied on, and she provided citations for each.

The three were book reviews written by psychiatrists that had been published in psychiatric journals. One was published in Psychiatric Services, which is a publication of the American Psychiatric Association. The second was published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, which is the “official publication” of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology. The third was published by the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease.

As is evident, these three sources tell of psychiatry’s response to Anatomy of an Epidemic, and in these book reviews, the psychiatrists are naturally eager to discredit the book and the presentation of evidence in it. Here, of course, is the journalistic problem: The New York Times article didn’t tell of book reviews by psychiatrists writing in psychiatric journals, but rather told of a scientific consensus derived from reviews in scientific journals. The implication is that these were “peer-reviewed” articles, whose authors did not have pro-psychiatry biases, and that they had detailed instances of my “cherry-picking” of data in Anatomy of an Epidemic. The sentence served as a “science has spoken” declaration by The New York Times, but it was a declaration derived from reviews that didn’t exist.

Once Barry informed me of her sources, I wrote Hilary Stout, Deputy Health and Science Editor at The New York Times. I admit I was initially pissed at this attack on Anatomy of an Epidemic, but after the first wave of irritation passed, I wrote to her because I was curious to see how The New York Times would defend this declaration.

In my email, I stated that the description of Anatomy of an Epidemic as having been dismissed in reviews published in scientific journals was “false” and “injurious to my reputation” and thus could be seen as libel. As such, I asked for a retraction. The line in the article did not inform readers that these “reviews” were in fact book reviews by psychiatrists that had been published in psychiatric journals. I said that I knew of no article that had ever appeared in any scientific journal that pointed out a specific instance of my “cherry-picking data.” I sent her several book reviews that appeared in scientific journals praising the book; I told her of the impact that the book has had; and I noted how the Investigative Reporters and Editors Association had given Anatomy its “best investigative book” of the year award in 2010.

In sum, I presented to The New York Times evidence that, if it had wanted to weigh in on the merits of Anatomy, then it could have considered the positive reviews, the impact of the book, the IRE award, and then worked all that information into a paragraph that also told about how psychiatrists, in their book reviews, had expressed negative, even hostile opinions about me and Anatomy of an Epidemic. That would have been a “fair” thing to do.

Stout responded rather quickly. “Thank you for your letter,” she wrote. “Ellen forwarded me the two emails you sent her yesterday as well. I have reviewed your concerns and the reporting behind the sentence in question, and I have consulted with other editors here. We stand by the language in the article.”

My first response to this depiction of Anatomy of an Epidemic, and the defense of it by Stout and her fellow editors, was to see it as an instance of dishonest journalism. Indeed, others who read the article described it to me as a “hatchet” job, a “smear” job, and that was my first response too. However, I think ultimately it is more helpful to see it in a different light.

There is, of course, an “evidence base” that resides at the center of the counter-narrative. While the three psychiatrists in their book reviews may have heaped ad hominem criticisms on me, the public can go to madinamerica.com today and find drug-resource pages related to the long-term effects of antidepressants and antipsychotics in adults, and stimulants in children. On each page there is a summary of the findings from a long list of studies that collectively tell of how the drug treatments worsen long-term outcomes, and there is a link to each study so the public can follow this trail of evidence.

This was the very trail of evidence that led Laura Delano to her aha! moment. She could see that there was research, much of which had been funded by the NIMH, that could explain the trajectory of her life once she was diagnosed.

However, The New York Times and most of the mainstream media is invested in the conventional disease-model narrative, which has two basic elements. That narrative tells of how research has proven that psychiatric medications are effective treatments, and tells too of how critics of the drugs can’t be trusted. Critics are said to have a bias toward the profession; they may be likened to conspiracy theorists or to Scientologists. The conventional narrative informs mainstream media that such critiques should be dismissed as lacking scientific credibility.

Those are the two conflicting narratives present today in our society, and The New York Times article lands in the midst of both. This is an article that tells of how it can be very difficult to withdraw from antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs, a theme that arises from within the counter-narrative. The article tells of a need to create support for people who want to taper from their medications, and thus, in a sense, it is opening up a discussion about the possible harms from psychiatric drugs. But, at the same time, the conventional narrative requires that the public be reminded that psychiatric drugs are effective, and that critics of psychiatric drugs can’t be trusted.

So how to write about Unshrunk and deprescribing of psychiatric drugs while still preserving the conventional narrative of the efficacy of psychiatric drugs? The sentence that tells of reviews in science journals dismissing the “analysis” in Anatomy of an Epidemic is when the article snaps back into the conventional narrative. Science has shown that the critics of the drugs can’t be trusted.

There are two other instances in the article where Barry takes pains to preserve the conventional narrative. You will find both in this paragraph, which describes studies that the Inner Compass website links to:

“A section on antipsychotics, for instance, cites studies that purport to show that people who take them fare worse than people who never take them or stop them. (This is misleading; people do not take them unless they have severe symptoms.) A section on antidepressants cites a study suggesting that they cause people to commit acts of violence. (The study was criticized for distorting its findings.)”

The article is informing readers that Inner Compass is linking to studies that can’t be trusted. The studies are “misleading,” or “distort” their findings. However, once again, it is easy to show that this dismissal of Inner Compasses links isn’t warranted, and instead, is best seen as deriving from a cognitive dissonance that arises when the conventional narrative of psychiatric drugs is challenged with references to published research. The research must be discounted if the conventional narrative is going to be maintained.

The first link in that paragraph is to a randomized clinical trial by Dutch researcher Lex Wunderink. The study was conducted in a cohort of first episode patients who had stabilized on antipsychotic medication and were randomized either to treatment as usual, which consisted of regular drug maintenance, or to a drug-tapering protocol. At the end of seven years, the recovery rate was twice as high for those randomized to the tapering protocol (40% versus 18%). The study provided RCT evidence that giving first-episode psychotic patients a chance to taper from antipsychotics can lead to much better long-term outcomes.

The second link is to a study by the Nordic Cochrane Center. The researchers there did a systematic review and meta-analysis of 130 randomized clinical trials and concluded that SSRI and SNRI antidepressants double the risk of suicide and violent acts. The New York Times article dismisses this study as having “distorted” its findings. But follow the link to the criticism of the study and you discover it goes to the Science Media Centre, and what most readers won’t know is that the Science Media Centre is funded in part by corporations and industry groups, including several pharmaceutical companies. And as critics of the Centre have noted, it often defends the “products of its funders” and does so with “canned quotes” from the experts.

So, in The New York Times article, Anatomy of an Epidemic is dismissed, a RCT study that found reason to offer psychotic patients a chance to taper from their medications is dismissed, and a meta-analysis of RCTs that concluded SSRIs and SNRIs double the risk of suicide and violence is dismissed. Moreover, in the same section that Barry disparages the research that Inner Compass links to, she states that psychiatric medications “remain the only evidence-based treatment for severe mental illnesses.”

It is easy to see why reporting on Unshrunk and the Inner Compass Initiative can promote a dose of cognitive-dissonance confusion for any journalist at a mainstream newspaper. On the one hand, the article is giving credence to the understanding that withdrawing from antidepressants can be very difficult, which is telling of possible harm from their use, which is part of the counter-narrative that is the context for Laura Delano’s book. On the other hand, The New York Times’ reporting on psychiatry is centered within the conventional narrative, which tells of drugs that are effective treatment for known “illnesses” of the brain, and that critics of that narrative are cranks or worse. That is difficult terrain to navigate, particularly since the institutional beliefs of the newspaper demand that the conventional narrative be protected.

Indeed, you see that clash of narratives in the more than 1000 comments to the article. There are hundreds of comments telling of how psychiatric drugs saved their lives and heaping disdain on Laura Delano and her husband Cooper for thinking that drugs can cause harm, and then there are many who tell of how they were harmed by drugs and are thankful for Laura Delano and her work.

Laura’s book is certain to provoke such cognitive dissonance in other reviews by mainstream publications. However, hers is a compelling story, and it will be interesting to see if her book succeeds in punching a hole in that cognitive dissonance. Moreover, book reviews are often written by people who are not employees of the paper, which allows for more freedom of thought, and so there is a possibility that such reviews will, at least to an extent, break free from that conventional narrative box.

Two Book Reviews

Even as I finished writing the first draft of this blog (on Thursday March 20), I was alerted to the fact that both The New York Times and The Washington Post had published reviews of Laura’s book that morning. The New York Times review is favorable, and I would say, fair. It provides a useful summary of her book and its themes, and in that regard, it does provide reason for a larger societal discussion on the merits of our current disease-model of care.

The Washington Post review is quite different in kind. It is vicious toward Laura personally and her book, and it depicts any hint of the counter-narrative—of a drug-based paradigm of care that can do harm—as irresponsible nonsense.

Anatomy of an Epidemic makes only a cursory appearance in the review, with the author Judith Warner writing:

“One of the first books she read was Robert Whitaker’s ‘Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America.’ It is one of many works by journalists over the past 15-odd years that have waged war on the psychiatric profession, often by building on the logical fallacy that if rates of mental illness are increasing and use of mental health treatment is increasing, then the treatment itself must be causing the illness.”

That of course is not the argument made in Anatomy of an Epidemic (see above). But in terms of preserving the mainstream narrative, The Washington Post, when it assigned the review of Unshrunk to Judith Warner, could have been confident that she would do just that. In her 2010 book We’ve Got Issues: Children and Parents in the Age of Medication, Warner argued that children, if anything, are underdiagnosed and undermedicated, with NAMI giving her an award for her work.

I have to confess that I wasn’t prepared for the nastiness of a review of Unshrunk like the one published in The Washington Post. It is vicious, and this can’t be seen as an instance of cognitive dissonance. You can see the torrent of abuse and expressions of hate toward Laura it unleashed in the comments section, and all I can say is that I think it is a disgrace that The Washington Post would publish a review that promoted that response. You can publish a review that is critical of a memoir, but I don’t think you should use the power of the press to publish a review that seeks to destroy the person and turn her into an object of public contempt.

Looking Ahead

I think it’s fair to say that the mainstream media’s response to Laura’s book is off to a muddled start. The New York Times, in its first article, did open a door to a new discussion, and yet, at the same time, took a shot at Anatomy that was designed to protect the conventional narrative. The New York Times book review, meanwhile, served to further push open that door a notch. The Washington Post review, nasty as it was, sought to slam that door shut.

As new reviews roll in, think of them as weighing in on a clash of narratives. Through that lens, you can see whether Laura’s book is helping to prompt a larger societal discussion about the merits of our disease model of care, or whether the reviewers are intent on shutting down such a discussion. Meanwhile, readers of Mad in America can read her book to make their own conclusions about its merits.

Thank you, Bob, for your thoughtful–as always–analysis of the NYT and WaPo reviews. It makes perfect sense that the WaPo reviewer would have gotten an award from NAMI–and yes, her “review” was much more of a take-down than a fair review. Yes, the tension between the mainstream narrative and Laura’s memoir is clear—-But as I always tell people who tell me their stories of success with psych drugs, “I respect the truth of your story. I hope you can respect the truth of mine.” Kudos to you and Laura!

Report comment

Thank you for writing a thoughtful piece on the current press surrounding Unshrunk.

I pre-ordered Unshrunk and it blew me away. It is brilliantly written. Laura tells her story with fierce courage and humility. She states she is not “anti-psychiatry.” The book is not an angry mental patient screed. She is reflective about the harm she caused her family and others without any self-flagellation that is central in most memoirs about mental health as well as most memoirs about substance abuse. It was a refreshing blast of fresh air.

Were I to sit and ponder, there’d still be details I could critique about her life and its difficulties, how it differs from my own experience, and how she frames her reckoning with those experiences. But this narrative is her own. To do so would be disrespectful to the writer, because that would be a personal attack.

To see such behavior from a professional “critic” of literature is appalling. The Washington Post review was personal, nasty and vindictive. The comments section was no better. I did notice on the Ellen Barry piece published Monday that there were some commenters who are desperate to have this conversation about psychiatric harm. I knew current US politics and its theater would be brought in to the criticism; as a left-leaning harmed patient and survivor of psychiatry, I can’t put into words how mind-numbingly defensive and uninformed most progressives are about this topic. It’s been very humbling. I feel as though we’ve all lost our way with respect to nuance and finding common ground.

On the bright side, I think more people are willing to have a discussion about psychiatry and mental health services. Offline I’ve been surprised how many will admit the system does cause harm.

I’ve come to believe those who want to shut down conversations critical of psychiatry and standard mental health treatment have their own agenda. They benefit in some way from the way things are — financially, socially, and emotionally.

Report comment

Thanks for sharing, since I’ve yet to read Laura’s book, but I do thank Laura for her courage, strength, and ability, to get her book published by a mainstream publisher.

“I’ve come to believe those who want to shut down conversations critical of psychiatry and standard mental health treatment have their own agenda.” And I do agree, “it’s all about the Benjamins.”

Report comment

Yes, the Washington Post review is horrible. Especially weird is that the critic works for an oligarch owned, president Trump-normalizing newspaper when he is at the same time trying to tarnish Laura Delano’s reputation by comparing her critical views of psychiatry to those of secretary of health RFK Junior and Trump.

Is Elon Musk with his self-disclosed “Asperger autism” who sticks to his ketamine anti-depressant prescription the serious guy, then?

Thank you for mentioning the “mind-numbingly defensive and uninformed […] progressives” when it comes to an understanding of the harm that is done in psychiatry and psychotherapy.

I am a left-leaning survivor of psychiatry and psychotherapy myself. This situation has led to cutting myself off from all my old friends of this group of people one after another.

The day came when I wasn’t able to listen anymore to their analysis of systemic oppression underlying everything and their claims of psychodynamics being a liberating discourse.

For them the horrible things I told them them happened to me in psychotherapy could neither be true nor being rooted in the systemic oppression inherent to the professional fields of social work, psychotherapy and psychiatry. (And where their mothers, sisters, fathers, best-friends, and boyfriends worked).

The problem, as they saw it, could only lie in my individually defective psyche. After that they went on with their critique of neoliberalism putting too much responsibility on the individual. It didn’t make any sense.

When this started to drive me more and more inwardly aggressive and added to the problems that I was experiencing in the wake of the maltreatment and abuse I had endured in psychotherapy that were similar to the symptoms described in a PTSD I knew I had to cut myself off from these people for good.

It’s so good to have Mad in America. Thank you all for the discussion here.

Report comment

“ “A section on antipsychotics, for instance, cites studies that purport to show that people who take them fare worse than people who never take them or stop them. (This is misleading; people do not take them unless they have severe symptoms.) A section on antidepressants cites a study suggesting that they cause people to commit acts of violence. (The study was criticized for distorting its findings.)””

Is a blatant lie as people are for sure put on antipsychotics without a single exhibition of psychosis. Abilify is marketed as a helper drug, an add on. It’s one of Americans top ten drug? So are they arguing that a gigantic percent of the population is psychotic.

This is still such a tiny scope of the problem told by a demographic that is always at the forefront of story telling.

Report comment

“A section on antipsychotics, for instance, cites studies that purport to show that people who take them fare worse than people who never take them or stop them. (This is misleading; people do not take them unless they have severe symptoms.)”

Is [this] a blatant lie as people are for sure put on antipsychotics without a single exhibition of psychosis.

Indeed it is a lie, since I was put on antipsychotics because a non-medically trained, child abuse covering up, psychologist thought all dreams are “psychosis.”

But when all who dream are “psychotic,” according to the scientifically “invalid” DSM “bible” believers, they’ve rendered their term “psychotic,” to be “irrelevant to reality” … just like the “mental health” industries’ DSM “bible” was claimed to be … way back in 2013.

Wake up, deluded DSM “bible” believers, please!

Report comment

“They’ may be positing that a large number of people are psychotic or need “mood” drugs. Look how the numbers of people taking psychiatric drugs has increased over the years since Prozac Nation. And how many doctors are trained (really trained) to help people get off this stuff? Keep up the good work Robert, we need you!

Report comment

I have just listened to Laura on an episode of a DarkHorse podcast (find it on your favorite source).

It caused me to wonder if I will get to know in my lifetime, the unraveling of what to me – has been a wide scale poisoning, of trusting people? Perhaps? I hope.

For me, also – it was the pharmaceuticals that caused the problem. I also, blame no one. Obviously, they didn’t know. And I also wish no ill will to those who believe these pills helped them.

Laura said something, we all (who have escaped the medical trap must know, though words are hard pressed to describe it) … in this article “Perhaps it wasn’t that she suffered from a mental illness, but rather it was her diagnosis and drug treatment that had caused her such suffering.” This is a head spinning moment.

For me, this moment was when I realized I had to quit those pharmaceuticals, or they would kill me. I had to place my faith in God, because the medical world of our times, simply doesn’t know.

She also speaks of learning to be an adult (she was diagnosed as a teen) off of the pills. I think for all of us, we must relearn “agency”. Being a good little patient, means doing what you’re told. Being a grown human means managing one’s own life.

I hope, for all the children, a balance becomes more readily accessible – between those who have been helped and those that have been harmed.

Report comment

I do agree we are seeing “the unraveling of what to me – has been a wide scale poisoning, of trusting people.”

Report comment

Fully agree. Re: your comment, “Being a grown human means managing one’s own life.” — I’m reading Thomas Szasz’s The Myth of Mental Illness and there’s a bit where he talks about how psychiatry installs passivity and obedience in patients: “It is as if the patient were saying: ‘You have told me to be disabled — to be stupid, weak and timid. You have promised that you would then love me and take care of me. Here I am, doing just as you have told me, it is your turn now to fulfill your promise!”

Report comment

“It is as if the patient were saying, ‘You have told me to be disabled — to be stupid, weak and timid…’”

That’s the implicit message I got LOUD AND CLEAR as a young adult when all I was trying to do was come to terms with a succession of family tragedies.

I’ve since learned I wasn’t the one “lacking insight”.

Report comment

Indeed, incorrectly assuming (and trying to brainwash) all their “clients” that they are “stupid, weak and timid” is a systemic problem for the DSM deluded “mental health professions.”

A systemic problem that makes an “a-s” out their “clients,” but also sometimes makes an “a-s,” out of the scientifically “invalid,” incorrectly assuming “mental health professionals” … and hopefully soon their entire, unGodly disrespectful, industry.

Report comment

I have long considered “The New York Times” to be the house organ of the mental health movement. It is surprising to me that they did an article on Laura Delano’s book “Unshrunk,” let alone a book review.

I take this to mean the editors thought the book was too powerful to completely ignore. But all of the coverage takes great pains to avoid the reasons why Laura decided to come off medications: she did not have a bona fide disease and the drugs did not cure anything. In short, psychiatric treatment was not medically necessary.

Neither “The New York Times” nor “The Washington Post” can say “the emperor has no clothes.” So they pretend to defend science against a band of unscientific quacks.

In fact, the newspapers are defending what David Wootton has called “Bad Medicine.” They are saying in effect that our expert doctors say their clinical judgment tells them that bloodletting is safe and effective, and we have all of these success stories to prove it! (Please don’t look at the bodies piled up in the corner.)

Those who object must be “anti-bloodletters”! Or flat earthers. Or Scientologists. Or anti-psychiatrists. There is no need to listen to them. We, the mainstream media, will not let psychiatry die in transparency.

Report comment

“Neither ‘The New York Times’ nor ‘The Washington Post’ can say ‘the emperor has no clothes’. So, they pretend to defend science against a band of scientific quacks.”

I think it’s called “business as usual”.

Report comment

” … Those who object must be ‘anti-bloodletters!’ Or flat earthers. Or Scientologists. Or anti-psychiatrists. There is no need to listen to them. We, the mainstream media, will not let psychiatry die in transparency.”

And us independent psychopharmacology researchers here say, let’s not let psychiatry die in transparency, let’s expose the psychiatric industries’ DSM lies … which are really big lies. And why the historically holocaust causing, continuingly harmful, scientifically fraud based psychiatric industry should likely die.

Report comment

The vitriol directed at Laura doesn’t surprise me. It was unrealistic to expect anything less at this point in time.

The hard truth is it’ll probably take at least another 5 or 10 years for public sentiment to meaningfully shift in the opposite direction.

But here’s the thing: there’s no silencing the bell Laura has rung.

Report comment

” … there’s no silencing the bell Laura has rung.” Let’s hope and pray.

As one who has met Laura in real life, and learned from meeting her that she’s a wonderful, empathetic, kind, truth seeking, and generous person … albeit I have yet to ask my local library to purchase her book so I may read it, and learn more about her journey.

Not to say people shouldn’t buy her book themselves, I may myself, but my bookshelves are getting pretty overfilled. But please do think about going and requesting her book at your local library, since that too could help her book sales (and our truth telling cause).

Although, at this late date, I’d say requesting Robert Whitaker’s, Moncrieff’s, Breggin’s, Gøtzsche’s, et al’s critical psychiatry books from your local libraries would be a good thing to do also, if they don’t already have them. Let’s try to fill the libraries with truth speaking critical psychiatry based books.

Report comment

What a wonderful suggestion, Someone Else! Seeing a particular book in a public library setting often has a way of gradually tempering people’s cognitive dissonance.

In any event, it’s a matter of getting the word out right now 🙂

Report comment

Well Birdsong, thank Boans, since he’s actually the one who came up with the suggestion, which I’m just repeating, because I thought it was a good suggestion too.

I guess my addition of “Let’s try to fill the libraries with truth speaking critical psychiatry based books,” was my creative marketing of what I thought was a good idea of Boans, but my first college degree was a marketing degree.

Nonetheless, we should both say thanks to Boans. And hopefully critical psychiatry, et al, people will go start requesting critical psychiatry and survivor books, at their local libraries.

Report comment

Yes, indeed, Someone Else. Let’s all hope more public awareness adds to the number of people willing to take a critical look at establishment psychiatry.

Report comment

Don’t be a victim of these confused vampires writing for the NY Times Robert – you are in denial over what you are up against. Namely, the living dead who grift as we destroy the Earth, confused vampires that ravage the corpse of our society as we all tear chunks out of each other out of our confusion manipulated by lies, and our hatred and greed. Save yourself Robert, and let’s all save ourselves. There is nothing that can be done for the magot infested corpse that was once natural social humanity. Even though these NYT journalists in this makes your blood boil, and mine, to take them on here is as useless as heckling the captain of the titanic for crashing into the rock rather then saving yourself and as many of those you can who you can help on the way. I’ll fling myself off the side with you into the pitch black freezing cold sea. It’s better then being pulled down by the vampires and drowned by greedy people trying to clamber over and stamp on you in order to try and get free.

Report comment

The mainstream reaction is utterly predictable.

Report comment

Thanks for all you have done, and do, Altostrata.

Report comment

I agree! Thank you!

Report comment

Anyone else here fall in the middle on this? I don’t think you can lump all types of symptoms and medications together, they each need to be evaluated separately. And I know there are both many who have been harmed by medications and also many who have been helped by them. Ultimately what we need is true informed consent of the risks and benefits to taking and not taking medications, and to have other options. As well as for the field of psychiatry to stop being ableist, sexist, anti-mad, etc. Everything is about balance and I feel like both sides are both a bit right and a bit wrong on this, with psychiatry being most in the wrong.

Report comment

Years ago, David Cohen published a model “informed consent” form for psychiatric treatments. I believe it was published in the “Journal of Humanistic Psychology.” He surmised that no one was doing anything like it and that no one given such a form would be likely to sign it. Here is my own version of an ideal informed consent form:

“You are being prescribed mind and mood altering drugs based on the false assumption that you have something wrong with your body and/or brain. You have been labeled with a psychiatric “disorder” that is not a disease, that has no reliability or validity, and that no one will ever admit is a mistake and remove from your medical records.

Though these medications and treatments may have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration as “safe and effective,” the science behind them has been repeatedly shown to be false and even fraudulent. No one has ever proven that any so-called “mental disorder” has a biological or genetic basis.

Once taking these drugs, you may feel better or worse or that they have had no effect. While they do have effects, they are not treating underlying diseases; they are not correcting unproven “chemical imbalances.” You should be aware that it is widely known that people who take pills or have treatments often feel better even if there are no medications in the pills or the treatments are shams; this is called “the placebo effect.”

Once you start taking a psychiatric medication, it will be very difficult to stop. However, psychiatrists refuse to call them “addictive,” instead saying that you may suffer a “discontinuation syndrome.” It may be dangerous for you to stop taking these medications because of the effects they may have while trying to taper them off. If the medications do not work, it is likely that you will be given more such medications. You will find it nearly impossible to get a psychiatrist or other doctor to stop prescribing your medication(s) or to help you to discontinue them.

You do not have a biological disease. You are experiencing “problems in living.” There are many ways to solve problems in living via non-medical approaches. Sometimes we have problems in life that are tragic and for which there are neither easy solutions nor solutions at all. Interpersonal harmony is not a given in life; it is a rare personal achievement.

While you have been told that your medical records are confidential, this is not true. If you use medical insurance, your diagnosis and treatment will be sent to a large credit-like bureau for medical information. This information will be accessible to life and health insurers, large employment agencies, and others.

Now that you have been given informed consent about these proposed treatments, do you agree to sign this form and undergo these treatments? There will be no penalty to you if you should refuse, and you will not be forced to take any of these treatments against your will.”

Report comment

Sounds largely what a truly informed consent form should say, for all psych “professionals” today. Thank you, Keith.

Report comment

Keith, this is brilliant. Thank you!

Report comment

“A Model Consent Form for Psychiatric Treatment,” was created by David Cohen and David Jacobs. It was originally published in Winter, 2000 by the “Journal of Humanistic Psychology”: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3233/JRS-1998-142

It has also been posted on the website of the Law Project for Psychiatric Rights: https://psychrights.org/research/digest/InformedConsent/DCohenmodelinformedconsentform.htm

Here is one paragraph from their article:

“We are inclined to think that no one who was so informed would consent. Of course, this is an exceedingly complex question. It would be greatly simplified if clinical psychiatry and clinical psychopharmacology rested on rigorous research and valid findings, showed genuine concern for the patient’s or subject’s bests interests, and operated in a mental health system designed to meet patients’ or clients’ needs. We have argued elsewhere in detail that this is not the case (Cohen, 1997; Jacobs, 1995; McCubbin & Cohen, 1996). If our analysis has any validity, no consent form will do. Nevertheless, therapists, clinicians, or researchers must obviously make a sincere effort to convey the risks, the drawbacks, the unknowns of psychiatric drug treament ‹ even if many prospective patients might understandably recoil.”

There are four fundamental principles of medical ethics: (1) Patient Autonomy; (2) Informed Consent; (3) First, Do No Harm; and (4) Patient Confidentiality.

While doctors may often violate numbers 2, 3, and 4, they rarely violate number 1. However, practitioners in the mental health field routinely violate all four.

Report comment

When you have been tortured without consent- medicated until your eyes rolled into the top of your head and akathisia so severe the soles of your feet became covered in blisters from the constant pacing. When you were prescribed antipsychotics because you were young and attempted suicide and doing so insured insurance might think you really needed to be incarcerated and pay for a longer stay, it it is really hard to be in the middle.

That being said, I am aware of my bias. I am also aware that what happened to me, happened to many, many others, and continues to occur every day.

A middle? As in true informed consent- starting with the invalidity of diagnosis and informed consent that the drug will damage brain tissue, perhaps irreparably? That would be a middle for me. I wouldn’t want people who like their medicine to not be able to have it, not at all.

That’s the point, people should have their personal autonomy respected, whether they choose to take any medication or treatment whatsoever.

They should not be manipulated or coerced.

People should have the right to know how the drug they are taking 1) acts upon the organ intended 2) any possible side effects 3) any true peer reviewed meta-analysis even if the results are not favorable 4) long- term possible consequences.

Thank God for Google Scholar, and websites like these. Those who have the desire can dig and find information for themselves.

Yet, there are those who in distress, with no access to any information other that what the “expert” wishes to declare, who are so very easily harmed. That’s what a lot of we in the comment section do not want. We don’t want others to suffer as we have.

Report comment

The evidence we currently have points to medicines causing significantly more harm than they have benefits. And when you look at their mode of action, it’s not really surprising, as they’re not really designed to be good for you in the first place. A lot of the benefits of the psychiatric medicines are just placebo, which can be very powerful. There is evidence that suggest that for some people, their symptoms go away simply with placebo. That’s good for them, it’s amazing really, but it doesn’t justify using such dangerous substances to create it. Even lobotomy had many grateful patients, even though they were just destroying their brains, because people really, really, really want to think it was good for them, for lots of reasons.

I don’t think the problem here is just the lack of informed consent. Yes, it is extremely important, it is necessary, and would be a huge part of the answer to the problems in psychiatry, and also people who want to use these psychoactive substances should be able to do so with it. But the narrative here is that patients are largely incapable of making decisions for themselves. The narrative is that patients don’t understand what’s going on and what’s good for them, and so the practitioner is the right person to make the call. (And by creating that narrative, and encouraging others to just ignore what the patients say, practitioners create so much stigma towards and pain and social exclusion for the patients, but that’s another story.)

I don’t think it is wrong to give, for example, a child or severely intellectually disabled person life-saving tooth surgery even if they don’t understand what it’s for. I don’t think it’s bad to give someone something actually necessary or objectively good, even if it has some risks, even if they can’t really consent. People in general don’t really think that, so if the “medicines” are even somewhat good, people don’t think informed consent is necessarily that important at the end of the day. It “saves lives” after all and “there’s no other way”.

Because of that, I think the message about “medicines” and other current biological “treatments” should be clear. Psychiatry does not have safe and effective treatments. There is no real evidence that they do. If they actually saved lives, that could be proven with data that doesn’t come from a science hoax by now. The harms exceed the benefits. The placebo-ridden, fundamentally unprovable anecdotes shouldn’t stop us from saying that.

The dangerousness of these medications would be included in real informed consent, but we can’t get to that, if most people don’t really understand why it’s so crucial in the first place.

The idea that these psychoactive substances are okay overall, sometimes they’re good for patients, sometimes they just don’t work and they may also cause harm – it doesn’t differ that much from the psychiatric narrative (or from how it just is in medicine). You can then justify the use of forced medications by saying that the patient’s judgement was clouded and the psychiatrist could expect the patient to benefit from them. This isn’t so, it’s clear they don’t generally really think so, and because of all that that narrative should be taken away. Also, patients need actually correct information when they are trying to make decisions for themselves.

Report comment

Another great review.. This is why I love Mad in America.. 🙂 It publishes ‘scientific’ research and reviews on ‘mental health’ and ‘psychiatric drugs and other harmful psychiatric treatments such as ECT’.. They work with valuable researchers, scientists, journalists, etc.. Open-minded and ‘commentators’ are given special respect..

I will try to obtain Laura’s book. (Unfortunately, things are not going well in my country.) As far as I understand… This book alone is one of the best examples of how psychiatric treatments do not work and can even cause harm..

(As a writer, I am also planning to publish a book soon under the title “Psychiatric drugs cause mental illness.” I will try to reveal the true relationship between the human body and the soul. In this book, I will also try to explain how millions of people around the world who use psychiatric medications may have been silently subjected to a ‘chemical lobotomy’ in their homes. Of course… I’m in the preparation phase right now. It’s not ready yet.. And I don’t know how successful it will be.. And right now, things are a bit chaotic in my country. People can’t talk anymore. There are political infighting. Frankly, I’m worried. So I won’t be able to say much.. Anyway..)

As a final word… People are injured and die from psychiatry. But these are blamed on other causes and are not recorded in the patients’ medical and death reports. Injuries and deaths are blamed on other causes. So.. Injuries and deaths resulting from psychiatric treatments are covered up. The medical world also covers up these injuries and deaths. Unfortunately…

Now politicians and the real medical world must open their eyes. Psychiatric medications and other harmful psychiatric treatments such as ECT must now be abandoned. In the treatment of mental illnesses, ‘non-drug treatment behavioral methods’ should be adopted. And as soon as possible. Without wasting any time. Best regards.

With my sincerest wishes. 🙂 Y.E. Researcher blog writer (Blogger))

Report comment

I love Mad in America, too! I am proud to be a lifetime donor for it!

Report comment

My family are also regular donors to MiA. MiA is an important, truth telling, website. Please consider supporting MiA, we need to support the truth telling journalists.

Report comment

Well said! Thank you!

Report comment

I was involuntarily committed for “bipolar” in 1989 and 1990 and have titrated from many of the same drugs as has Laura. Zyprexa has been the hardest to titrate from and I’m still on a small dose of it around 2mg. daily. I’m a retired educator who also won nomination for Congress in West Virginia. Humbly, my life’s trajectory compares quite favorably when compared to that of the history of psychiatry. The Zyprexa and Lithium caused me much physical harm. Hence psychiatry feels like something being put over on me rather than something that was helpful. It seems to me that these supporters of psychiatry would rather someone be broken rather than have them talk back to psychiatry.

Report comment

Russian roulette

Bob,

Yes, there are patients who say they feel and fare better when taking psychiatric drugs and there are patients who feel and fare worse. The same is true of those people who ‘play’ Russian roulette.

You demonstrate how difficult it is to persuade the public that taking psychiatric drugs is, at best, risky, like being offered a daily go at Russian roulette; the prescribing doctor gives the revolver to the patient to take home and neither of them knows where the bullet is until it is too late.

We are preaching to the converted.

Clive Sherlock (https://www.adaptationpractice.org/)

Report comment

“Russian roulette is not the same without a gun,” my subconscious self has been singing that for seemingly over a decade.. And it is a song about psychiatry’s iatrogenic harm, IMHO. But, of course, one can’t prove such. However, I do NOT believe God is ignorant of what is going on.

Report comment

Society is not yet ready to face the truth about psychiatry and the harm they’re causing.

Several psychiatric survivors commented under the NYT book review of Laura’s book.

Many bravely shared their similar experiences in the psychiatric system and of being harmed by SSRIs, antipsychotics and other psychiatric drugs and how they were forced to get help from online support groups who knew more about drug tapering than their doctors.

They shared stories of decades of their lives stolen from them and the neurological injuries caused by longterm psychiatric drug usage.

Instead of showing support and empathy to these psychiatric survivors, they were met with hostility, invalidation and flat out rejection that psychiatry could ever do this to anyone.

I was saddened to see it unfold in the comment section but not surprised at all.

Psychiatry has such a firm grip on the general public.

Plus they’re backed by a multi-billion dollar pharmaceutical industry.

The reaction to Laura’s book shows me the world will continue to defend the mental health industry and no amount of truth will wake them up.

“You have to understand, most of these people are not ready to be unplugged. And many of them are so inured, so hopelessly dependent on the system, that they will fight to protect it.”

Report comment

I truly admire Robert Whitaker’s ability to maintain the integrity and dignity in the heat of these minefield mental health discourses, and by extension, safeguarding the vital work being accomplished at MIA- at no small personal cost to him I would imagine.

Here’s a question perhaps worth asking: is the level of political coverage, i.e., levels of facticity, representation, and ‘critical’ analysis provided by the NYT ‘reporting’ over the last few decades, substantively different than their mental health ‘reporting’? The implications should deeply concern everyone, IMO.

Lastly, I just read Rachel Aviv’s book, “Strangers to Ourselves”, last week. I found Aviv’s profile of Laura Delano both entertainingly informative and frustratingly withholding; of which, now, having read Roberts’ article, I understand why. I’ll have to read Laura’s book now, if for no other reason to see just how counter-narrative it really is! My guess is not so much, and hope I’m dead wrong. That said, I figure the more negative or muddled reviews “Unshrunk” garner from establishment outlets, the more relevant and vital Laura’s story will actually be.

Report comment

Ladies and gentlemen of MiA, let’s all go out and request our libraries carry

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/59808605-strangers-to-ourselves

And Laura’s book

https://www.amazon.com/Unshrunk-Story-Psychiatric-Treatment-Resistance/dp/1984880489

from our local libraries. They sound like an intriguing couple books, and such is a benign thing anyone who feels like a dejected psych survivor could do, as too many of us here, were made to feel we were.

But please do buy the books, too, if you can afford them.

Report comment

Thanks, Bob, for your important discussion. I didn’t get to read the Washington Post review because it’s behind a paywall. However, I think the New York Times review was also harmful– simplistic and implying that Laura’s work to help people get off drugs just stems from her personal experience. It did not at all take into account the ways she repeatedly broadened the discussion from her experience to an examination of the flaws in the clinical trials and other ways in which psychotropic drugs have been adopted rather cavalierly.

Also, Ellen Barry is very wrong about the way anti-psychotics are prescribed. I see them being increasingly used as part of drug cocktails for people who are depressed. It happened to me.

Report comment

“Excuse me Mr Putin, you left something in your pocket. It’s an orange man in a white house.”

Report comment

Thank you so much for this article, Bob! I divide Laura’s book into two parts: the first part being that for the first 23 chapters she had suffered a lot for so many years seeing no hope for her future, and the second part that starting from Chapter 24 and for the rest of the 13 chapters she read your book, met you in person, started to wake up to reject the system and got to live a life she had not imagined possible before.

Report comment

Thank you, Bob! I realize I shouldn’t have been surprised, but I was horrified to see the large number of negative, and sometimes personally insulting, comments on both of the reviews as well as the Barry story. The mainstream narrative which is driven by $ and big corporations (big pharma, newspapers, the medical industry) has been concerning for a long time. These articles and reviews are nevertheless opening the door for new people to witness the harms of psych medications and to question their personal relationships to these drugs. For years, many of us have been well aware of the dangers of getting caught up in the mental health system. Mad in America and Unshrunk have introduced many new voices into this important conversation. Thank you, Bob and Laura and Cooper!

Report comment

Bob, I just read the NYT review of Unshrunk. I could not find a March 18 article by Ellen Barry, only a March 20 article by Casey Schwartz

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/20/books/review/unshrunk-laura-delano.html

I’m confused. Did they replace Barry’s article or am I missing something?

Report comment

Ellen Barry’s article on Laura Delano, “Leading a Movement Away from Psychiatric Medication,” is still on the NY Times website, though it is behind their subscriber paywall:

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/17/health/laura-delano-psychiatric-meds.html?searchResultPosition=2

Report comment

OK. Thanks.

Report comment

Deep gratitude to you, Bob– for describing the landscape and the context. What major media fails to grasp. Your 2010 book, the website MadinAmerica, and your ongoing talks, blogs, etc. help readers to understand and hang onto the greater truth. Not so easy when major media aligns with Big Pharma. Thank you for continuing to do the deep diving to uncover and write about the truth. Thank you for all your efforts to educate other journalists. And, thank you for all you do to bring current research to those of us wanting the larger truth, e.g., what are the longterm effects of the use of psychotropics? Who is doing the research? Where can we find it? Your POV from your research and connections to others offering context in the community is of immense value.

Report comment

Thank you for this well considered response, Bob. I truly appreciate all your work. It seems to me interesting that many pharmaceutical companies share similar shareholders to the New York Times, such as Blackrock.

Report comment

Thank you Bob Whitaker. I am sorry that your book received such opprobrium in those reviews from the NYT and the Washington post rag. I wonder if the attack was a form of ‘democratic’ opposition to the current administration in the US. Perhaps your book and the conclusions in it were conflated with the opinions of the MAGA crowd such as Robert F Kennedy Jnr’s opposition to allopathic medicine generally and Elon Musks’ comments about SSRI’s. My heart sinks to see people such as them and others I won’t mention fronting the damage these drugs do viewpoint.

However overall, I still do not understand the hostility directed at Delano and yourself. When a psychiatrist currently in the ‘mainstream’ like Dr Chris Palmer who advocates the keto diet for curing mental illness himself loudly bemoans the fact that these drug treatments do not work and in many cases prolong the illness by damaging the mitochondria, it is hard to understand the reasoning behind such blinkered thinking.

Perhaps some of these people are on the drugs themselves? And of course these drugs do ‘work’ on symptoms- some of them can numb you; some of them can help you sleep; some of them stop hallucinations/delusions; some of them can calm anxiety and that is why many commenters probably state that their drugs are life saving to them. But they don’t seem to be able to grasp that taking something for a short period can be helpful but that the longterm usage of a drug that can lead to chronicity of mental illness. That does not seem to penetrate at all.

I would like you to know that people such as myself salute your doggedness and courage and I salute people like Laura Delano too. It is hard to stand out against the crowd however educated and elite. Human beings are really awful on balance with a few exceptions.

The truth will come out eventually the way it did with the early generation barbiturates and benzodiazapines although no apology will probably be forthcoming. It would be pretty horrifying if war/tariffs made these addictive drugs unavailable to the millions worldwide currently taking them. Then the fun would really begin.

Report comment

Well said! Thank you!

Report comment

“But they don’t seem to be able to grasp that taking something for a short period of time can be helpful but that the long-term usage of a drug that can lead to chronicity of mental illness. That does not seem to penetrate at all.”

Who wants to hear that a supposed “miracle drug” might not be all it’s cracked up to be?

“The truth will come out eventually the way it did with the early generation barbiturates and benzodiazepines although no apology will probably be forth coming.”

Yes. What’s happening now has happened before and most likely will happen again.

All this does is prove that those working in advertising are far cleverer than those working in medicine.

IMHO.

Report comment

This is a really interesting article and thank you for publishing. The New York Times may have done an okay job, but—as they often do—they included one or two lines clearly designed to bait their demographic.

What’s truly interesting is how, in our culture, people treat psychological research as if it were written by Nature or handed down like gospel. But in psychology, the group being studied is often more important than the result. You can conduct research on college students or on people from society’s so-called “soft underbelly,” and both groups might end up with the same diagnosis. Yet the contexts are so radically different that it makes you question the validity of the conclusion. Shouldn’t the environment factor in more prominently?

Take bipolar disorder or addiction, for instance. Some studies might suggest these people end up homeless, addicted, or worse. But the reality is that many are simply suffering—in entirely different contexts. The research flattens their humanity into a category.

Now, take Laura Delano. She’s being personally attacked—and that’s what tends to happen in our supposedly scientific society. If you say something without the backing of a thousand voices, without a credential or a title stamped beside your name, your words are dismissed as meaningless. But here’s the irony: the doctors who created the DSM diagnoses often noticed patterns in just one or two clients before launching research to validate what they already believed. You see where I’m going with this?

Critics accuse Laura of having certain “connections”—but let’s not pretend that connections are only valid when they come from MDs or PhDs. One kind of “authority” is born into; the other is built from reading. The hypocrisy is almost too absurd to take seriously.

Laura was placed on multiple medications between the ages of 13 and 27—a time when her brain was still developing. Of course that had an effect. Now, as an adult, she’s pointing out a glaring gap in the system: medications are prescribed freely, but the medical field is terrified of confronting the fact that sometimes, these medications simply don’t work.

She’s not offering a cure of meds only—she’s exposing a failure of a system. And that’s why they’re coming after her. Meanwhile, people are becoming mini-chemists just to undo the damage done by the very professionals meant to help them. Let that sink in.

There may be nothing organically wrong with Laura now—or even if there is, she’s finding ways to manage it on her own terms and it seems she is not alone in it. The issue is that her natural development was interrupted by medication, and she’s daring to say so out loud. And while the New York Times and The New Yorker occasionally acknowledge the problem of the medical field, the common excuse remains: “It takes too much time.” Too much time to consider a life beyond meds.

Let’s talk about suicide. There’s a high risk of suicide when people don’t take medication, do take it, and when they come off it. Yet only the middle scenario—those currently medicated—gets the system’s attention. The other two are ignored, as if they don’t exist. Why? Because they lie outside the medical model’s comfort zone.

Laura is poking the bear by asking the obvious: if suicide is a risk no matter what, what exactly is the system offering as a solution? If suicide is the common denominator, and doctors only treat the medicated, then the burden is on the medical field to come up with answers for the others too.

But instead of engaging with her message, critics attack her personally. Isn’t that telling?

It’s also interesting to note that Laura isn’t even directly challenging the diagnoses themselves. Most critiques of psychiatry tend to stop there—focusing on the treatment process rather than questioning the foundation of the project itself. But wouldn’t it be even more powerful if we went a step further and critically dissected the diagnoses? That’s where the real challenge to psychiatry begins (and why they strongly come out against anyone speaking about it). I smile as I write this, because even Mad in America might hesitate to go that far—after all, that’s when the true power of psychiatry is put under the spotlight – what is bipolar actually?

I tried that myself and was blocked so strongly I was not surprised, and I am in the field! Simply I was told implicitly my story itself was not believable without medication! Is not interesting she took medication and being framed as quack, and I did not and though not truly framed as quack but rejected the same for challenging a label that did not fit my “observable” life! The whole system does not work without first labeling you to disable you and if you challenge the labeling, forget about it! You are marginalized!

At the end of the day, it’s painful to witness, but all these reveal the truth: they don’t really care because for now they do not see worthy capital for investing to care those who refuse to fall inline without liability!

And that is the real story here.

Report comment

I remember learning about the release of the NYT article through browsing the inner compass initiative website or maybe it was the inner compass exchange and I was exited to read it !! I clicked the link and here i was readîng .. but … as I was reading, I became also confused, I was reading and felt i was reading conflictîng information, on one end, some things seems to be written to inform of Laura view and experience and on another hand it was crushing its strénght. I must say that i was disappointed with the article, confused and wasnt sure where It wanted to go, what was the point, purpose..

Laura voice, work and experience is so valuable, powerful, sound, honest and helped me enormeously over the years that i was disappointed not to see it coming through clearer on the article.

I wonder if Bob will make a legal action regarding the libel on the nyt article.

I wonder also about the validity of orher nyt articles now that i know what they are about on mental health.

Report comment

Kudos Mr.Whitaker for your resolve and critical intelligence.

In its unwillingness to behave with intellectual honesty,

its willingness to contravene the oath to do no harm,

to market its wares like snake-oil salesmen,

to befuddle the MSM with pseudo-science,

…..well we’re dealing with a corrupt authoritarian regime.

Psychiatry is a neo-liberal cult.

Power to the People.

Report comment

I just finished listening to Unshrunk. I was glad I was able to hear the voice of this courageous, intelligent and self-reflective woman. I loved how it intertwined her narrative with researched facts. I am sure the book was cathartic for her but she went beyond just an interesting, exceptionally written story of hope, resilience and self-compassion to love for others who suffer as she did. Her compassion toward the psychiatrist who “treated” her was beautiful. To feel betrayed and harmed but to be able to see the humanity in another is truly inspiring and what is needed more in our society. The psychiatrist was a product of professional identity ingrained in her from medical school and residency training that she had maybe too much investment in socially, professionally and financially to challenge. Since I read Anatomy of an Epidemic and have followed many thoughtful blogs and readers’ responses, the veil of deception has been lifted and just no going back. That Laura got some terrible attacks, a very reactive response tells me you hitting on that “cognitive dissonance”.

I truly hope that Laura knows how amazing her book and she are. I wish her and her beautiful family much good health, peace and love.

Report comment